Writing Chicana/o History (Rosales Castañeda)

Writing Chicana/o History with the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project (2012 revision)

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 The Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project (hereafter referred to as the Seattle Civil Rights Project) has allowed a city to retell its rich, multicultural civil rights narrative. Since its inception in 2004, it has produced a wealth of information that allows Seattle’s history to be retold through research reports, digitized documents, and dozens of oral history videos, allowing the fusion of oral history tradition with the newly emergent digital research project medium.1 In 2005, coming off the initial release of the newly minted Project, a group of undergraduate students, myself included, met with University of Washington (UW) history professor, Dr. Jim Gregory, and UW Ph.D. candidate, Trevor Griffey, to dialogue on expanding the Civil Rights Project to include the local ethnic Mexican/Latino community in Seattle. This meeting resulted in what became the largest archive documenting the Chicana/o Movement2 outside of Southwest United States. Nationwide, this reverberated throughout academic circles as a model for undergraduates to produce and write digital history for K-12, college, and public audiences.

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

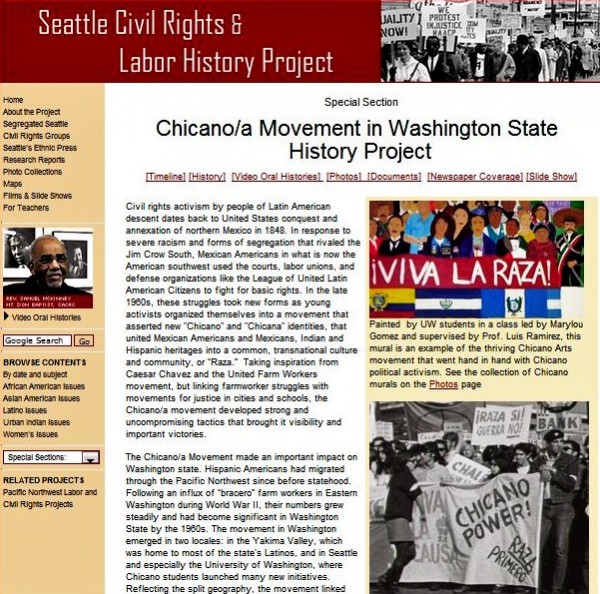

Figure 1: Click to open the Chicana/o Movement in Washington State History Project home page (Courtesy of the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project)

Figure 1: Click to open the Chicana/o Movement in Washington State History Project home page (Courtesy of the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project)

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 From the onset, the “Chicana/o Movement in Washington State History Project” (hereafter referred to as the “Chicana/o Movement Project”) was intended as a point of departure; an exploration of a local narrative long relegated to obscure, unpublished materials and oral histories passed down from one generation to another. For many Latinos in Seattle and the Pacific Northwest, the thirst for knowledge was tempered by a sense of isolation from the ethnic Mexican/Latino cultural hubs in the Southwest and East Coast as well as a sense of historical omission in regional narratives. The need for addressing this dual marginalization proved to be the impetus for initiating the Chicana/o Movement Project research.

¶ 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

Latinos in the Pacific Northwest

Interest in Chicana/o activist history at the University of Washington (UW) was central to our contingent of freshman students as early as 2002. Most of us arrived from Eastern Washington, with some from the Seattle area, as we formed the leadership of the UW Chapter of El Movimiento Estudiantil Chicana/o de Aztlan (The Chicana/o Student Movement of Aztlan)3 or “MEChA.” For many, this was the first time we came together with other like-minded youth to organize around educational access, economic justice, civil and human rights. The previous leadership graduated the summer before we arrived. Their departure left an organizational vacuum that prompted us to take over the reins of the leadership to ensure organizational continuity.4

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

Fig. 2: MEChA de UW group photo in front of Suzzallo Library at the University of Washington on April 5, 2006. The Author is in the first row, second from right. (Image from Author’s Personal Photo Collection)

Fig. 2: MEChA de UW group photo in front of Suzzallo Library at the University of Washington on April 5, 2006. The Author is in the first row, second from right. (Image from Author’s Personal Photo Collection)

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Among the initiatives we pressed forth were educational meetings to share skills and knowledge as well as to train ourselves in organizing strategies. We understood that there was a relation between ourselves and the space we inhabited. Far removed from the cultural hubs in the Southwest, yet part of a cultural Diaspora that adapted to its new surroundings, we imagined a way of being and collaborating with other communities that represented a smaller portion of the local population, in contrast to other places in the South and East.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Our first encounter with this ethnic Mexican/Latino narrative in the Pacific Northwest came through a class instructed by Dr. Erasmo Gamboa.5 Though the class introduced material that we had not seen in Washington state history textbooks, the material mostly related the rural experience. The urban narrative existed, as we later found out, in various journal articles, masters theses, document collections, and published ephemera that were inaccessible to many readers in our community. As a means of addressing this issue, we undertook the task of consolidating material pertinent to our history in Seattle and the University of Washington.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 As this project was underway, we received an e-mail from an alumnus and California State University at Northridge graduate student. While researching on Google, he stumbled upon former UW Activist, Jeremy Simer’s web article, “La Raza Comes to Campus,” published from Dr. Jim Gregory’s Independent Research Seminar at UW. The discovery of this article impacted how we viewed digital media in collecting this history. We knew that the best way to preserve and build on our work was to make it accessible to anyone curious about the subject. The intent was to make the work available through our organization’s website. After serving out my term as the chapter co-chair I looked toward fleshing out this idea and was successful in acquiring a research fellowship for 2005-2006. I argued the project would “aid in incorporating scholarly work from the Pacific Northwest into the study of Latinos on the West Coast, enhancing the already existing historical narrative.”6 I was also fortunate to receive a second fellowship from the UW’s Center for Labor Studies, which was presented at the center’s annual ceremony, where I met Dr. Gregory. As a consequence of having a sizeable class from 2002, we had students looking to initiate senior projects. We now had the research contingent and resources to unearth our collective vision.

¶ 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

Fig. 3: Student contingent from UW MEChA at a Rally Before an Anti-War March, c. 1971 (Image Courtesy of the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, UW)

Fig. 3: Student contingent from UW MEChA at a Rally Before an Anti-War March, c. 1971 (Image Courtesy of the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, UW)

¶ 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

Urban Activism in Seattle

The project intended to examine the local movement’s unique character, in relation to its spatial confines in a city long known for its vibrant history. Unlike the cultural nationalist current prevalent in cities and communities along the Southwest, activity in Seattle mirrored the Third World and internationalist tendencies of the San Francisco Bay area. Further, unlike the southwest, activity in Seattle and other communities in Washington State differed as there was no significant record of social and political mobilization within the ethnic Mexican/Latino community.7

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Upon reading the primary sources, it was clear that our project would shift focus. A survey of this narrative from early rural farm worker activism to later urban movements had not been written. As we discovered, original writings had been fragmented in four-to-five year increments. Furthermore, much of this story lay in a tapestry of documents buried in archives since at least the 1970s. This forced us to utilize a three pronged approach with researchers conducting oral history interviews, digging into archival material and newspaper articles, and others writing material and digitizing rare, tattered documents that sat in MEChA de UW’s file cabinet for decades. We did this to weave these writings on farm labor unionization, student strikes, urban and rural activism and cultural aesthetic movements into one historical survey that covered the period from 1965 to 1980.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 With the project taking form, local interest in the research slowly surfaced. Nationwide, polemic debate around immigration seeped into mainstream parlance. In April of 2005, the “Minuteman Project” began conducting armed patrols of the U.S.-Mexico border under the pretext that borders were porous and susceptible to “terrorist organizations,” a reflection of anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant hysteria of the post 9/11 era. Soon this staunchly nativist group began patrolling the northern border, along Washington State’s northern counties. This right-wing anti-immigrant formation in turn influenced policy makers, who by late December of 2005 passed House Resolution 4437 (commonly referred to as the “Sensenbrenner Bill,” after the legislation’s primary sponsor, Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin).8

¶ 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0

Fig. 4: A Flyer for the May Day 2006 March in Seattle. The march drew an estimated 50-65,000 participants. (Image courtesy of El Comite Pro-Reforma Migratoria Y Justicia Social)

Fig. 4: A Flyer for the May Day 2006 March in Seattle. The march drew an estimated 50-65,000 participants. (Image courtesy of El Comite Pro-Reforma Migratoria Y Justicia Social)

¶ 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0

Fig. 5: Seattle Police Officers close major streets as marchers make their way through Downtown Seattle on May 1, 2006 (Image from Author’s Personal Collection)

Fig. 5: Seattle Police Officers close major streets as marchers make their way through Downtown Seattle on May 1, 2006 (Image from Author’s Personal Collection)

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 In response to this highly controversial, draconian legislation, immigrants and their allies protested en masse in the spring of 2006 for what was perhaps the largest wave of demonstrations in a generation in the United States. In the Seattle area, immigrants came out in force as never before. In a meeting, Dr. Gregory communicated that during this time, search engine queries for information on the immigrant marches led to our rudimentary project site (mostly still under construction). We were months from completing the project and the need to tie in events from the present day to our narrative was a reminder that regionally, the narrative was still being written. Nevertheless, in spite of lacking an accessible established historical narrative infrastructure, the demand for this information was visible. These events made our nascent project even more noticeable and further fed interest in regional scholarship.

¶ 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0

Teaching and Researching History in the Present Day

Since 2005, scholarship on Latinos in the Pacific Northwest has resurfaced from the last flurry of activity in the early-to-mid 1990s. Of note, one of the most recent collections of essays, Memory, Community and Activism, edited by Jerry García and Gilberto Garcia,9 expands this examination of ethnic Mexican communities in the Pacific Northwest by including cross-cultural collaboration in labor, the cultural significance of art in public space, the role of the Church in community activism and most critical, the role that gender has played in community organizing in the region. In addition, Jerry García also published a book illustrating the formation of Quincy, Washington’s Latino community.10

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 Along with the aforementioned books, there are also recent articles, theses and Ph.D. dissertations that focus on Chicana and Chicano experiences in the Pacific Northwest. Aside from the Chicana/o Movement Project at UW, other research projects in existence or transferred to digital format include the Chicano/Latino Archive hosted by The Evergreen State College Library, and the Columbia River Basin Ethnic History Archive hosted by Washington State University at Vancouver.11 The proliferation of these new sources within the last few years in turn complemented and helped strengthen the Chicana/o Movement History Project’s visibility. Our work confronts collective amnesia within Washington state history textbooks, and challenges textbooks on Chicana/o history to include the stories of northern communities. In effect, the literary definition of “borderlands” takes on different meaning as the experience at the U.S.-Canadian Border region becomes a part of the larger historical narrative, augmented by the use of digital media to teach this unique history.

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 It has been over five years since the Chicana/o Movement in Washington State History Project was officially unveiled in August of 2006. Three years later, a sister project, the Farm Workers in Washington State History Project, went live in September 2009.12 Much like its predecessor, it followed the same pattern and worked to acknowledge the history of union organizing for Washington’s socially and economically marginalized farm laborer population. Besides influencing additional research projects, the Chicana/o Movement History Project has also been used as required reading for U.S. history classes at the University of Washington, Whitman College (a liberal arts college in Walla Walla, Washington), Washington State University, Western Washington University, and other institutions, namely, the University of California at Los Angeles and the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, among others.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 These digital history projects, in addition to the larger Seattle Civil Rights Project, also have been featured in the American Historical Association’s Perspectives publication, various oral history and diversity oriented publications, and newspapers ranging from the Seattle Times and Seattle Post-Intelligencer, to the New York Times, USA Today and the local National Public Radio (NPR) affiliate, KBCS.13 The research has also been listed in the Civil Rights Digital Library and reviewed by the National History Education Clearinghouse.14 Likewise, the local Public Broadcasting System (PBS) Affiliate, KCTS Seattle, produced a brief documentary detailing the experiences of the first class of Latino students at the University of Washington, entitled “Students of Change: Los del ’68,” which used much of the background material researched by our project.15

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 Perhaps most profoundly meaningful for many of us who produced the project are comments and e-mail messages from community members who have stumbled upon the project or were referred to the site by a teacher or professor. For many, it was their first introduction to the local history of the Latino community in Washington State. They validated not only the struggle in producing the material, but also the reason for why it matters and why it merits further research. The project was among one of the first nationwide to fuse academic writing and public history on the open web. Even more remarkable, perhaps, is that this project gave undergraduate students the opportunity to produce Chicana/o scholarship and has drastically changed the way that this history is taught in the State of Washington.

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 About the author: Oscar Rosales Castañeda is an independent scholar/activist based in Seattle, Washington. He was a student organizer at the University of Washington and participated in many social justice issues. He has contributed writing for the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, and was previously a contributor for HistoryLink.org. Presently he serves as Communications Director for El Comite Pro-Reforma Migratoria Y Justicia Social, a social justice organization based in Seattle.

- ¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0

- For detailed information on the project see: “About the Project” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/about.htm. ↩

- The “Chicano Movement” in the United States was at its essence, the rejection of assimilation into the larger dominant culture in the U.S. that sought to erase all semblance of cultural distinction (e.g. customs, language, music, ancestral knowledge) while simultaneously keeping the community in a state of second-hand citizenship that kept many locked in a cyclical poverty, disempowerment, and racism that was commonplace for many communities of color in the United States prior to the formation of the Civil Rights Movement. See George Mariscal, Brown Eyed Children of the Sun: Lessons from the Chicano Movement, 1965-1975 (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2005), 250. ↩

- MEChA is a student organization that has over 400 loosely affiliated chapters throughout the United States. See: “About Us: Movimiento Estudiantil Chican@ de Aztlan,” http://www.nationalmecha.org/about.html. ↩

- In Washington State, the emergence of a youth movement first took root in rural Central Washington’s Yakima Valley with the emergent farm worker movement in 1966 and 1967 and established itself in Seattle with the first significant recruitment class of Chicana/o students to the University of Washington. See Jeremy Simer, “La Raza Comes to Campus: The New Chicano Contingent and the Grape Boycott at the University of Washington, 1968-69,” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/la_raza2.htm. ↩

- See “Erasmo Gamboa,” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/Erasmo_Gamboa.htm. ↩

- Oscar Rosales Castañeda, “McNair Project Proposal” document in the author’s personal papers collection, June 6, 2005. ↩

- Oscar Rosales-Castañeda, Maria Quintana, and James Gregory, “A History of Farm Labor Organizing, 1890-2009,” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/farmwk_history.htm. ↩

- “HR 4437: Border Protection, Antiterrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act of 2005,” Bill Summary, The Library of Congress, http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d109:HR04437:@@@L&summ2=m&. ↩

- Jerry Garcia and Gilberto Garcia, eds., Memory, Community and Activism : Mexican Migration and Labor in the Pacific Northwest (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2005). ↩

- Jerry Garcia, Mexicans in North Central Washington (San Francisco, CA: Arcadia Publishing, 2007). ↩

- Chicano/Latino Archives, Evergreen State College Library, http://chicanolatino.evergreen.edu/; Columbia River Basin Ethnic History Archive, Washington State University at Vancouver, http://archive.vancouver.wsu.edu/crbeha/home.htm. See also Oscar Rosales Castañeda, “Bibliography: Farm Workers in Washington State History Project,” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/farmwk_bib.htm. ↩

- “Special Section: Chicano Movement in Washington State History,” http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/mecha_intro.htm, and “Special Section: Farm Workers in Washington State History Project,” http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/farmwk_intro.htm, both in Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, University of Washington at Seattle. ↩

- “News Coverage about the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project,” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/publicity.htm. ↩

- Civil Rights Digital Library, http://crdl.usg.edu/topics/boycott_direct_action/; National History Education Clearninghouse, http://teachinghistory.org/history-content/website-reviews/24033. ↩

- “Students of Change: Los del ‘68” KCTS9 Seattle, 2009, http://video.kcts9.org/video/1491354319/. ↩

Comments

Comments are closed

0 Comments on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

0 Comments on paragraph 15

0 Comments on paragraph 16

0 Comments on paragraph 17

0 Comments on paragraph 18

0 Comments on paragraph 19

0 Comments on paragraph 20

0 Comments on paragraph 21

0 Comments on paragraph 22