instructions for authors (September 2011)

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 7 Drafts of essays accepted for our open review phase have now been uploaded to this site and assigned to a password-protected WordPress account in the name of the lead author. Follow these directions (and view the video below) to finalize your digital essay. All edits must be completed by Thursday, September 22nd, in order for us to review and make them available for early commenting the following week, with the official public launch scheduled for October 4th. If you have any questions about the instructions below, post a comment or email the editors.

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

Enhancing Your Digital Essay:

When revising your essay, bring our common theme on “writing history” to the forefront, as this is the thread that binds together all of our works. Make specific case studies and individual examples more meaningful by addressing broader questions on how and why we write about the past in the digital age. Also, take advantage of our online format by incorporating screenshots with links to sources, or open questions that invite public responses, into the body of your essay. Most importantly, as you finalize your essay, reflect on your writing process: does publishing your ideas in an open-review web-book influence how you write?

¶ 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0

View our video tutorial on how to edit your Writing History essay in WordPress, with additional details explained below.

¶ 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

Logging into your account:

To edit your essay, log in with your assigned username & password for the Writing History site. If you need assistance, email the editors.

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Go to the Dashboard and select Pages to view your draft essay, and click the title to begin editing.

¶ 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

¶ 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0

The Editing Page:

Resize the editor window to fit your screen by dragging the bottom-right corner icon, and look for these essential components of your essay:

- ¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

- The Short Title is assigned by the editors to fit into the abbreviated online Table of Contents window. Please do NOT modify it, but feel free to email us if you wish to suggest a revision of a similar or shorter length. The short title will not appear on your essay page.

- The Long Title will appear at the top of your essay page, and you may modify it as you wish.

- The Author Byline should name all authors, and may be modified as you wish. When published, it will appear immediately below the Long title.

- The Author Bio will appear at the bottom of the main essay text. Please insert 1-2 sentences per author, with links to personal web pages if desired.

- Page Title Visibility should remain hidden, because this setting displays the Long Title in place of the Short Title on your published page.

- The Word Count for your essay (including notes) must remain below 5,000 words. If your essay exceeds this number, we may either remove it from consideration for the volume or arbitrarily cut any text beyond the limit.

- The Save Draft button retains changes as you edit. Feel free to log out and log in again as you wish.

- The Preview button displays how your page will appear after it is published by the editors.

- After you have finished ALL editing, press the Submit for Review button to notify the editors that your revisions are complete and pending final review. (If you accidentally press the Submit button before finishing, please email us and request that your essay be reset to draft mode.)

¶ 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

Click to view larger image in the same window.

Click to view larger image in the same window.

¶ 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0

Editing Text, Footnotes, and Links:

When editing your essay in WordPress, each paragraph stands as a separate block of text. Our CommentPress plugin uniquely identifies each block, so that readers may attach a comment to it. Prior to the deadline, you may add or delete any text you wish, but do not attempt to indent paragraphs. After the deadline, all of the essays will be “locked in” by the editors to avoid any conflicts with the commenting process.

¶ 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

We automatically converted all footnotes from Microsoft Word into a format that can be read by our WordPress footnote plugin. In the body of the text, each footnote appears in this standard format:

![]() On the published page, each footnote reference is automatically displayed at the bottom of the essay, like this:

On the published page, each footnote reference is automatically displayed at the bottom of the essay, like this:

¶ 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0

![]() To add more footnotes, be sure to follow the standard format: open-bracket, number, period, space, and the text of the note, followed by a closed-bracket. The space between the period and the text of the note is important! Be sure to use rectangular brackets to mark the beginning and end of your footnote, but do not insert them anywhere inside the text of the note. Instead, use parentheses “( )” inside the note.

To add more footnotes, be sure to follow the standard format: open-bracket, number, period, space, and the text of the note, followed by a closed-bracket. The space between the period and the text of the note is important! Be sure to use rectangular brackets to mark the beginning and end of your footnote, but do not insert them anywhere inside the text of the note. Instead, use parentheses “( )” inside the note.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 When creating a new WordPress footnote, which number should you insert? In most cases, simply use the number “1”, as we have done for most of your essays. The plugin automatically displays all notes in numerical order (1, 2, 3. . .) at the bottom of the page, regardless of the number you insert inside the brackets. There is one exception: if you duplicate the text of any note (e.g. using “Ibid.” more than once), then assign it a new number (such as “2” ) to avoid confusing the plugin.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 We rely upon the Chicago Manual of Style as our general guide, and we recommend using the free Zotero tool to manage your citations.1 At this stage, please do NOT insert a bibliography of sources at the end of your essay. After the open review period, if your essay is selected for the final manuscript, we will require authors to upload their bibliographies in Zotero format.

¶ 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0

![]()

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 We encourage authors to insert links to external sites in their text and footnotes using the “link” tool above, with two reminders. First, if embedding a link in the main text, also add a footnote with additional source information and the full URL, to assist future readers if a link no longer functions. (For example, see the Chicago Manual of Style and Zotero links with footnotes above.) Second, when linking to an external site, add a brief title and check the box to open in a new tab/window, so that readers may easily return to the original page.

¶ 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

¶ 19

Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0

Inserting Visual Media:

Consider ways to enhance your essay by selectively adding visuals with links, such as screenshots of other websites, images of source materials, examples of student work, or video segments. There is no limit on the number of visuals that you may insert in this online essay. However, if your essay is selected for the final manuscript, there is no promise that the Press would publish any of them in its online or print versions. Make sure your writing stands on its own two feet, with carefully-chosen visuals serving as enhancements. Moreover, as the author, you are responsible for certifying that your digital essay meets all fair-use copyright guidelines. For more information, consult a reputable guide such as the U.S. Copyright Office or the Stanford University Copyright & Fair Use site.2

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 a) The ideal visual image should be in JPG or PNG format, less than 1MB in size, and saved on your hard drive for future reference. If fair-use guidelines permit, you may create a “screenshot” image from another web page, using built-in commands or free tools for Mac or Windows.3

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 b) Insert your cursor in the text where the image should appear. To upload a copy of your image to the web, the simplest method is to load it directly to our WordPress site by using the Add Image button above the editing toolbar. Select the image from your hard drive to be uploaded to the Media Library. (Small images upload so quickly that you may not even realize that they’re done.) It is NOT necessary to press Save all changes.

¶ 22

Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 c) Select the Media Library tab, scroll down to your desired image (it shows those uploaded by all contributors), and press Show.

¶ 24

Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0

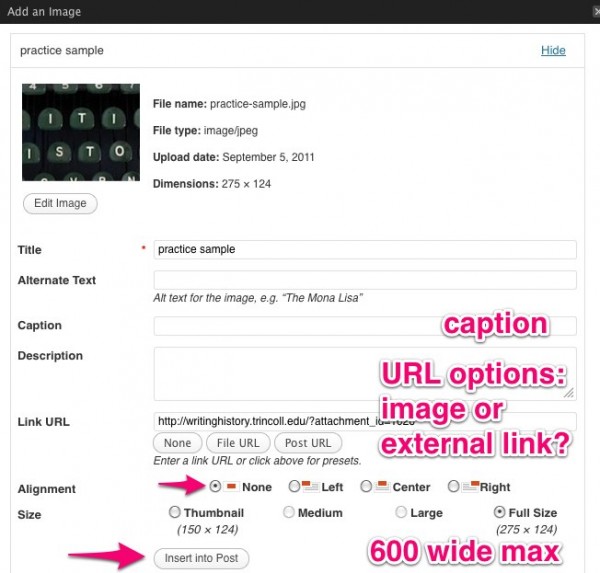

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 d) Edit these important settings for your image:

- ¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0

- Caption is optional but recommended for source information. Also, if you choose to link the image to an external site, mention that source here.

- URL options: what should happen when the reader clicks on the image?

- ¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0

- If you want the reader to see a larger version of the image, simply leave the default URL as-is.

- Or, if you want to reader to be sent to an external web page, insert the target URL here.

- Alignment: “None” is recommended, especially if you insert a caption.

- Size: The maximum width of images on our site is 600 pixels wide. If your image exceeds this limit, please choose either thumbnail, medium, or large (max 600), NOT full size.

- Insert into post

¶ 27

Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0 e) To make edits to an image after it has been placed on a page, click it and select the Edit Image button in upper-left corner. (Tip for image links to external sites: In the Image edit window, click Advanced Settings tab, scroll down to Advanced Link Settings, and check the “Open link in a new window” box.) To delete an image from the page, click the red Cancel symbol. (Due to the limited access settings, contributors may upload images, but may NOT delete them from the Media Library.)

¶ 29

Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 f) To insert YouTube, Vimeo, or Flickr images or video into a WordPress page, simply insert the URL into the text of the page, which will automatically embed it. See more details at WordPress Codex on Embeds.

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0 WordPress is one of the easiest tools to learn for editing web pages. Yet sometimes problems arise that can be difficult to solve. Please feel free to email the editors if you need assistance in preparing your essay.

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 If problems arise while editing your page, try switching from the Visual to the HTML view to identify the issue, or email the editors.

- ¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0

- University of Chicago Press. “The Chicago Manual of Style Online, 16th edition”, 2010; Center for History and New Media, George Mason University. “Zotero”, 2011. ↩

- U.S. Copyright Office. “Fair Use”, 2009. http://www.copyright.gov/fls/fl102.html; Stanford University Libraries. “Stanford Copyright & Fair Use Center”, 2009. http://fairuse.stanford.edu/. ↩

- See tips on Wikipedia. “Screenshot”, 2011. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Screenshot. ↩

Because part of this exercise is to give us all a chance to reflect on the larger writing practice publishing in this format involves, I thought I would add this reflection not so much as a complaint (although it might be construed as such) but as a comment on kinks in the process that perhaps should be worked out over time.

By requiring us to edit using the Word Press system rather than by revising on our own computers, the process in effect captures our scholarship in a way that might not be desirable in the long run. Say I make some revisions to my essay here, maybe even substantial revisions. And then say that my essay is eventually rejected for the volume (perhaps because I am an annoying, uncooperative contributer who leaves critical comments in the comment boxes). I am then left with my best product revised but not accepted–and stuck in a format that makes for laborious back translation to whatever word processing or other publication system that I might want to use in future as I try to find a home for my languishing, rejected essay.

What I am suggesting here is that the introduction of this step undermines or makes more difficult the old “turn your rejected essay around in 24 hours and send it to a different journal” approach that is sometimes urged on scholars to make us less thin-skinned.

In the short term this does not bother me, because I signed on to this project in part to force myself to learn something about how these new processes work. but in the long run it might discourage my participation in a project where publication was not more likely than it appears to be in the Writing History in the Digital Age project is.

Thanks, Amanda, for your constructive criticism about one of the key steps in creating a born-digital volume with WordPress. You’re right that authors should be able to export and convert their WordPress essays into whatever format they prefer. Technology should be a tool to help us do our work, not an obstacle that stands in our way, and we’re still figuring out how to get there.

Here’s what we’ve learned so far. When we needed to transform your Microsoft Word essays into a WordPress-friendly format, Katie Campbell, a Trinity student research assistant, discovered how to code a Microsoft Word Macro to automatically convert footnotes. Currently, she’s looking into ways to do this in reverse, from WordPress back to Word, using your essay as the test case If successful (and this remains to be seen), would that satisfy your concerns?

Thanks, Jack, for the quick reply.

I was thinking of more than footnotes when I wrote this. I was also thinking of other aesthetic and substantive edits. The changes I made in my essay between original submission and this week’s process were fairly minor, but I already don’t remember them and therefore would have to essentially re-read and remake those other changes in my document–unless the whole document could automatically reflow back into my word processor.

I do think that this raises an interesting question that is part of the larger Digital History transformation (revolution?). That is, to what extent do we all need to become tech specialists?

I thought about this in two different ways recently.

First, our computers have gotten so complicated, that I was delighted to be able to call in someone from the UWM IT staff to take care of a couple of fixes my desktop and laptop needed this week. The desktop problem was one I could not possibly have solved on my own, as it involved opening up the box and moving around pieces. But the laptop problem I could probably have solved on my own–if I had wanted to learn how to download a driver and make it work. Instead I saved space in my own brain for history stuff and let the tech people use the expertise they had already developed.

Second, I was talking with a colleague about the History and the New Media course that my department has on the books but has been taught only once. I was considering the possibility of teaching it (later rather than sooner) but she said that I couldn’t possibly–because the course involved teaching HTML. I suggested that there were other ways of thinking about the course that did not require extensive technical knowledge.

I suppose that the question opened up here is to what extent doing (not just writing) history in the Digital Age requires us to develop technical expertise. We’ve all more or less learned to use word processors and email the same way we learned to use telephones and photocopiers (within limits). But if my time is limited, do I want to do the kind of investigation that Katie Campbell did in this case, or do I want to use my free hours to do more historical research, writing, and teaching?

Pardon my delay in responding, Amanda, as I was. . ., um, er, working on making sure that our web technology is working smoothly for the upcoming public launch. So yes, you’re absolutely correct that digital history requires us to spend some time and energy learning new skills. Openly sharing info about these skills on the web (such as the link to Katie’s Word Macro conversion above) helps others save time and devote more energy to our primary focus: doing history. Remember, one broader goal of this online project is to find better ways to publicly share our scholarship and improve its quality with community feedback. If some of us can work together to create better tools and processes to benefit all of us, I think it’s worth the extra time. Remember, it was only a couple of decades ago when the stereotypical historian wrote his manuscript in longhand and handed it to his secretary to type up. Are you proposing that we roll back to that era? If so, I’ll need to start searching for a tweed jacket and smoking pipe. You don’t happen to have one that I can borrow, do you?

As I started to see comments appear on my essay, it dawned on me that this concern may hold even for this format–depending on how extensively I revise if the essay is accepted here.

A possible workaround, that I now can’t test because the essays are locked, but which I suppose might be possible just by viewing source code, since on a quick look at this page it seems like most of the styling is CSS. Either by copying the content ‘div’ out of the source code, therefore, or by copying the code from the editor window once that’s available again, paste the HTML behind your essay here into a Notepad file or your HTML editor of choice if you have one. Read that into Word or your word processor choice. Hack away as necessary. Won’t that do it?

Testing my own source code hack above, I find that it more or less works. There are paragraphs and paragraphs of HTML styling that you would want to prune out but the text comes out intact, and indeed if you’ve got comments expanded in the sidebar they do too, though in a different ‘div’. It would obviously be simpler and cleaner with the editor re-enabled. But, as long as it can go up on a webpage, you can grab that text back…