Visualizations and Historical Arguments (Theibault)

Visualizations and Historical Arguments (2012 revision)

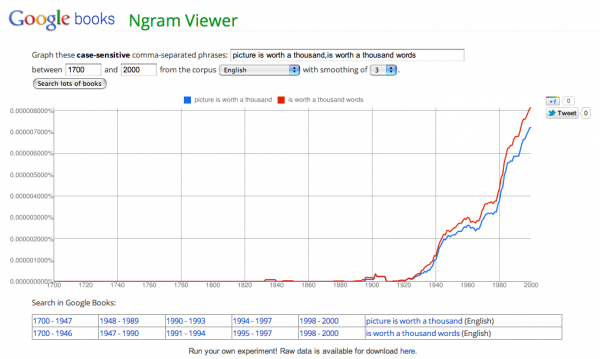

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 The popular phrase “a picture is worth a thousand words” is a relatively recent coinage, but the idea that images can be an effective complement to or substitute for written description, narrative, or analysis is probably as old as writing itself. In the European tradition, illuminated manuscripts and incunabula incorporated images, some of which conveyed messages related to the text and some of which were mere adornments. By the late sixteenth century, linkage of image and print reached a kind of apotheosis with the publication of emblem books, in which each page consisted of an image, a motto, and a pithy verse that jointly communicated moral precepts.1 Western historians have always made use of visualizations in this broad sense. Reproductions of pictures of the main biographical figures referenced in a book or other objects that figured prominently in the narrative appear in many historical works. Though the connection of these illustrations to the arguments of the book were often implicit rather than explicit, the text sometimes drew direct attention to elements of the pictures, so that the reader’s understanding was enhanced by close attention to the images.

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

Figure 1: Click to enlarge the Google N-gram on the recent rise of the term “a picture is worth a thousand words”

Figure 1: Click to enlarge the Google N-gram on the recent rise of the term “a picture is worth a thousand words”

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 When the term “visualization” is used today, it usually refers to an image derived from processing information — often but not always statistical information — which presents that information more efficiently than regular text could. Scholars quickly recognized the potential of computers to help process that information and display the results in an easy to interpret format. David Staley has argued for a sharp distinction between these visualizations as “the organization of meaningful information in two- or three-dimensional spatial form intended to further a systematic inquiry” and images as a “supplement or illustration to a written account.”2 Staley’s definition implies two distinct uses for visualizations in the digital age: as a means of quickly identifying patterns in large data sets during the research process that can open new lines of research and test qualitative assumptions, and as a way to enhance the presentation of arguments, moving beyond what it is possible to display in two dimensions on paper. Visualizations created for the first use may or may not appear in visual form in the final product. This essay is primarily concerned with visualizations as historical arguments in the second sense: how do we deploy the visual capabilities of the computer to show what we wish to communicate? It is slightly more ecumenical in defining visualizations than Staley is, in that it sees all uses of visual information to communicate an argument or narrative beyond the meaning of the words in text as forms of visual argument. It argues that visualizations necessarily have a rhetorical dimension and that the principal challenge facing historians who wish to use visualizations in their work is to align the rhetoric with the audience’s ability to follow it. The key dimensions of a visualization are the density and the transparency of its information — density being the sheer amount of useful information the visualization conveys and transparency the ease with which that information can be understood by the reader. We have become so accustomed to the visual vocabulary of print books that we scarcely register the visual conventions on which almost all historical work relies, such as the footnote indicated by a small number or asterisk. By now, we are also perhaps so familiar with standard web-page layouts that we no longer notice most of the visual cues that indicate the site structure, especially the relation of one page to another achieved by hyperlink. But many historians still have a print mentality when it comes to information dense graphics. When designing graphics, authors have to consider how much background information the reader brings to the visualization. The development of more complex visualizations has increased the gaps between expert and novice interpreters, which raises challenges for historians who seek the most effective visual approach.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 The problem of information density in visualizations is not a new one for historians. Even the most conventional nineteenth century political histories made use of three important visualizations: maps, timelines, and dynastic charts. It is, after all, much easier and more informative to create a chart of lines of descent to the Kings of France than it is to describe the lineage in paragraphs of “begats.” Each of these forms of visualization evolved a distinct visual vocabulary, with periods of experimentation and innovation producing visualization schemes that most modern historians now find completely transparent, with earlier visual dead ends now completely forgotten. Daniel Rosenberg and Anthony Grafton have recently shown how experimentation with designs of chronologies helped produce the modern streamlined edition of the timeline and information rich variants by the end of the eighteenth century.3

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 The emergence of the social sciences in the nineteenth century and the ability to work with large data sets created demand for new ways of visualizing information beyond maps, timelines, and genealogical charts. Processed numerical information was best expressed in tables, charts, and graphs. Mathematics, natural sciences, and social sciences that employed statistics were at the forefront of the development of charts and graphs. History was a consumer, not a designer, of most of these new visualizations – and mostly a sparing consumer at that, since economic and social history lagged behind political history as an area of research. Simple charts and graphs like pie charts, line graphs, and histograms were not difficult to interpret and their visual conventions became part of what any ordinary reader would be expected to follow. As statistical analysis became more sophisticated, the visualizations that resulted became more and more central to the argument. In some cases, the visualization made interpretation possible. These success stories demonstrated the worth of statistical analysis and visualization. Perhaps the most notable example is John Snow’s map of the incidence of cholera in an 1854 London outbreak, which helped plot the source of the outbreak at a single water pump in the neighborhood.4 Snow’s cholera map showed that visualizations could serve as both narrative and analysis. Authors began to experiment with ways of using visual clues to tell complex stories about events, increasing the amount of information that could be conveyed in a small space and thereby overcoming the limitations of two-dimensions in print. A noteworthy example of innovative presentation was Charles Joseph Minard’s Carte Figurative des pertes successives en hommes de l’Armée Française dans la campagne de Russie 1812-1813 of 1869, which shows the advance and retreat of French troops in Russia on a scale map while showing the changing size of the force due to death and desertion through the thickness of the line representing the force.5

¶ 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

Figure 2: Click to enlarge Carte Figurative, by Charles Joseph Minard

Figure 2: Click to enlarge Carte Figurative, by Charles Joseph Minard

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 The conditions confronting the troops during the retreat are also illustrated by a timeline of winter temperatures graphically connected to the map-based chart. Though Minard was a civil engineer, not a historian, he was able to construct a very powerful narrative of the events of Napoleon’s march on a single page. Minard’s chart is often cited as a model example of information visualization because it is easy to understand, even for people with little background information on the topic or quantitative skills. The challenge for visualization is to be transparent, accurate, and information rich. Minard’s information rich visualizations set the standard for both transparency and accuracy in the kind of work that could be done before computerization.

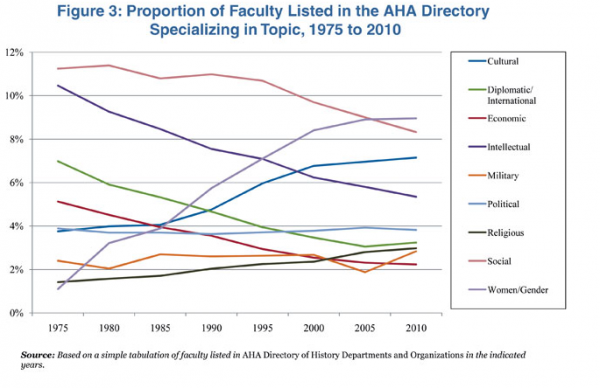

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 As noted above, historians were mostly consumers of statistics-based visualizations from the social sciences rather than innovators in constructing new kinds of visualizations. The advent of “cliometrics” and Annaliste total history in the 1960s forced more historians to become conversant with quantitative methods. Though the Annaliste approach to total history predated widespread use of the computer, much of the first wave of social scientific history relied on statistical packages like SPSS and SAS to process large amounts of data. The most determinedly quantitative works often had several pages of tables, most of which would be referenced in the text, but not always at the precise page that made the link between text and table most obvious. Instead of working as a driver of narrative, many of the tables and graphs produced in quantitative works of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s sat inert on the page, functioning more like the biographical pictures included in early historical works than as an integral part of the argument. Toggling between explication and evidence slowed reading considerably, so much so that readers of quantitative histories of the era sometimes broke into two broad groups: those who read the text and assumed the charts and graphs confirmed what was said there and those who read the charts and graphs while paying scant regard to the text. To be sure, many more historians developed the ability to rapidly interpret a greater variety of statistical representations. It became possible to use a scatterplot with a line of best fit or a Lorenz curve comparing inequalities with a reasonable expectation that most readers would be persuaded by the results visible in the charts, without requiring significant textual explication. But most social histories continued to rely primarily on bar and line graphs as their most prominent visualizations. And the fact that the statistical tools deployed often embedded assumptions that were inapplicable to the messiness of actual historical processes lent a false aura of scientific precision to very tentative conclusions. Many explanations have been offered for the relative decline of social history since its heyday in the 1970s, but a failure of imagination in the integration of visualizations with text based arguments may have contributed to the decline.6

¶ 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

Figure 3: The relative decline of “social history” among historians, in chart by Robert Townsend (2011)

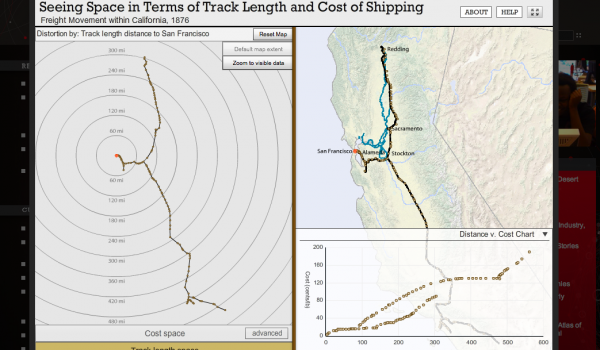

Figure 3: The relative decline of “social history” among historians, in chart by Robert Townsend (2011)

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 While historians debated how to incorporate statistical methods into scholarship, statisticians were becoming more self-conscious about how the results of analysis were being used. This attention to how quantitative information was presented first came to the attention of most humanities scholars with the publications of Edward Tufte in the 1980s. His three key works, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (1983), Envisioning Information (1990) and Visual Explanations (1997) placed the aesthetics and explanatory power of graphs and charts under closer scrutiny.7 It was Tufte who was most responsible for renewing attention to Minard’s Carte Figurative. Tufte’s main target in these books was what he called “chartjunk,” unnecessary clutter and contrived images that made visualizations confusing and sometimes deliberately misleading. Chartjunk was mostly associated with news and business publications in what today are called infographics. Historians, like social scientists writing for scholarly publications, tended to avoid visual embellishments of charts and graphs, but they did have to be attentive to ensuring that legends were clear enough that readers were not deceived by how information was displayed. Even accurate information can mislead if it is presented in a way that creates false visual cues. For example, inexperienced readers might need some guidance with a logarithmic chart so that they do not mistake an exponential change for a linear one. And sometimes, visualizations can be shaped to seem more conclusive than the underlying data actually warrant. For example, if a line graph showing differences ranging from 65 percent to 85 percent has its baseline set at 50 percent rather than zero, it leads people to see the differences in values as starker than they actually are. These issues of what one might call rhetorical honesty in the formulation of visualizations were compounded for historians and other humanists by the hard choices that were required to generate the data to be processed in the first place. As Gibbs and Owens note in their contribution to this volume, historians have traditionally been told to mask the twists and turns of the research process in their finished work to make their argument as strong as possible.8 This traditional approach can make any visualization seem like the product of a black box. Their proposal to share both data and methods in as transparent a manner as possible can have the additional benefit of making those visualizations easier to understand because the logic of how and why it was generated is visible.

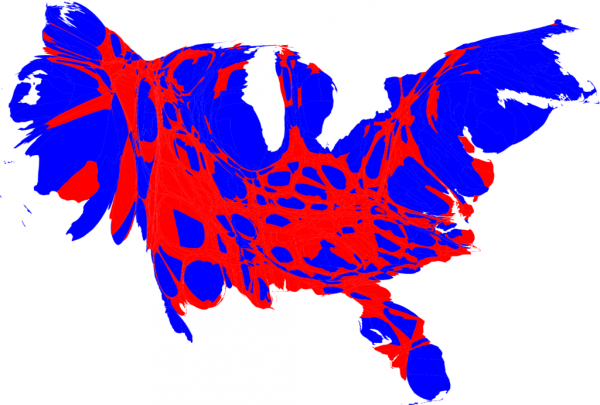

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Information rich maps are a particularly good example of the challenge of balancing honesty in visual rhetoric and clarity and persuasiveness. One often has to come to a map visualization with sufficient background information to “read through” peculiarities of delivery. For example, maps of presidential elections that appear in almost any textbook of American history typically color in each state according to which candidate received the electoral votes. It’s understood that the visual impact of the color contrast might over or understate how close the vote actually was. Some states are large in area but small in population, others, the other way around. There are ways to make maps that account for those differences. For example, a cartogram adjusts the size of geographical areas to make them proportional to their populations, while a choropleth map uses shadings of color to indicate the strength of the victory in a given area.9 The two adjustments, cartogram and choropleth, can be combined to further the information density. Unfortunately, the distortions of the cartogram when combined with the choropleth can also make the information harder rather than easier to interpret without a very high level of prior knowledge. This raises the question whether it is hard to interpret such a visualization because the format of combining cartogram and choropleth is unfamiliar. Most historians have probably encountered a choropleth map and a cartogram in a print history book or contemporary source in the course of their research, but probably have not encountered the two combined. Or is it hard to interpret because it makes unreasonable demands on the background information of the reader?

¶ 12

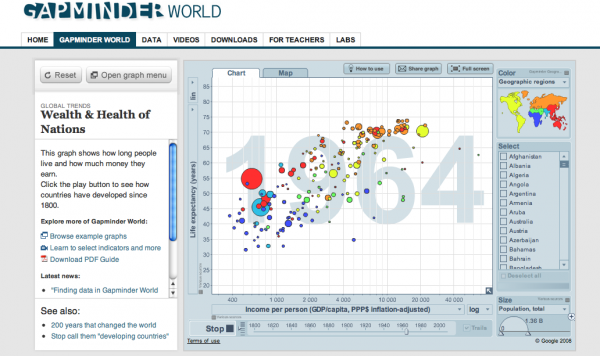

Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

Figure 4: County-level Cartogram of 2008 Presidential election results, map by Mark Newman.

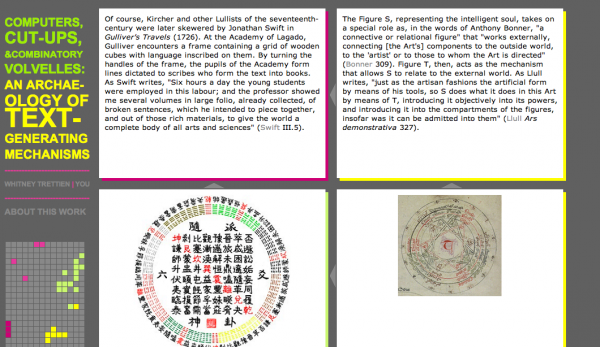

Figure 4: County-level Cartogram of 2008 Presidential election results, map by Mark Newman.

¶ 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0

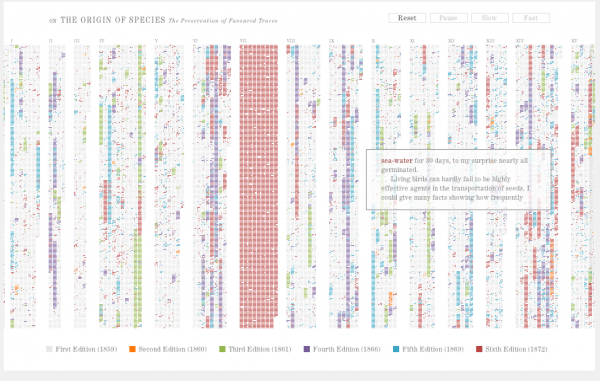

Figure 5: County-level Choropleth Cartogram of 2008 Presidential election results, map by Mark Newman.

Figure 5: County-level Choropleth Cartogram of 2008 Presidential election results, map by Mark Newman.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 The question of whether a visualization is hard to interpret because it is unfamiliar or because it relies on unrealistic expectations of background information assumes greater importance because digitization allows for even greater information density and novelty of form. Geo-spatial locating of information has been one of the richest areas of development in digital humanities. Complex visualizations based on maps are emerging as part of a “geo-spatial turn” in the humanities.10 One particular way that geo-spatial information density can increase is by animating it, adding time as another dimension of visualization. Just as a map can make 1 inch = 1 mile, an animated timeline can make 1 second = 1 year. A simple combination of animated map and timeline can create a powerful narrative without any text at all. A brilliant example of this is the animated map of the 2053 nuclear explosions between 1945 and 1998 created by Isao Hashimoto, which dramatically narrates the contours of the nuclear age.11 Aside from the title, there is no background information associated with the animation. The only text in the piece is in the legend, which emerges as each new nuclear power first explodes a device. Sound, not words, is used as a second way of highlighting the data points. Yet despite the absence of background information text, almost anyone watching the animation will come away with a deep understanding of the key features of the nuclear age. Only a modest background knowledge (such as knowing who the main antagonists in the Cold War were) makes the presentation of what might seem dry factoids not only informative, but moving.

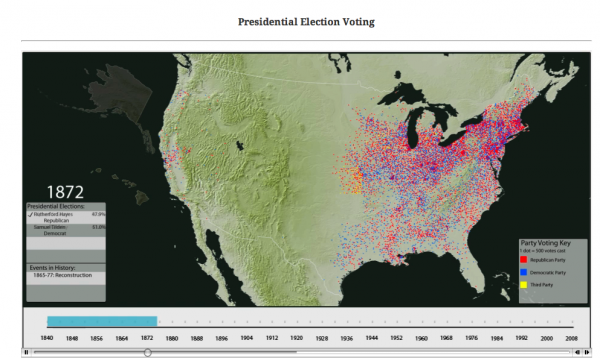

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 Hashimoto’s animation of nuclear testing cannot be manipulated by the user, aside from pausing and resuming the animation. Edward Ayers has coined the term “cinematic maps” to describe map based animations that show the process of change over time.12 The University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab has taken the traditional maps of presidential elections from 1840-2008 and turned them into an animated sequence.13 These maps try to overcome the information distortions caused by population differences and the electoral college by providing not only county level votes, but a Dot Density Map that shows the aggregated votes of 500 voters.

¶ 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0

Figure 6: Click to open Dot Density Maps of Votes for President, 1840-2008, from “Voting America,” Digital Scholarship Lab, University of Richmond

Figure 6: Click to open Dot Density Maps of Votes for President, 1840-2008, from “Voting America,” Digital Scholarship Lab, University of Richmond

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 Instead of adjusting the size of the geographical area to make it fit the voting pattern, the dot pattern reflects the density of votes in each region. Still, it is easy to imagine how this information could be converted to cartograms and choropleth maps of presidential elections to tell yet another story about changing voting patterns over the decades.

¶ 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

Figure 7: Time, distance, and costs of shipping in 19th century California railroads from “Railroaded,” Stanford Spatial History Project

Figure 7: Time, distance, and costs of shipping in 19th century California railroads from “Railroaded,” Stanford Spatial History Project

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 As part of Stanford’s Spatial History Project, online visualizations have been created to accompany Richard White’s recent book on the development of the trans-continental railroad.14 This project is particularly interesting for understanding the impact of digital humanities on current historical practice because it is directly associated with a print work and seems likely to serve as a template for future hybrid productions of print and digital. It is also closely aligned with a still more expansive set of visualizations from the Stanford Spatial History Project about the themes of the book collected under the heading Shaping the West.15 There are twenty-six different visualizations included at the site, sixteen of which are animated. Not unexpectedly, several of the animations are simple plotting of space and time like the animations described in the previous paragraph. But others complicate the visualization by layering information in innovative ways. For example, one visualization reframes shipping distances in California in terms not just of track length, but also time to delivery and cost. And even though the animations have been created as an accompaniment to an academic work, they offer an interactive opportunity to the reader that those other animations do not. Readers can customize the presentation of data to isolate issues of particular interest to them, rather than depending on the author to frame the question being answered. Interactive engagement with a visualization is yet another innovation made possible by digitization.

¶ 20

Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0

Figure 8: Networks of Boards of Directors of Western railroads, from “Railroaded,” Stanford Spatial History Project

Figure 8: Networks of Boards of Directors of Western railroads, from “Railroaded,” Stanford Spatial History Project

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 As historians ask more complex questions about the data they have assembled, the problem of how best to present the information requires more thought. In the Shaping the West site each visualization has an “about” or “help” tab that functions as a legend and guide to the information contained in the site. The visualizations are not self-explanatory. A particularly complex visualization links the geography of the railroads with a network diagram of the boards of directors and sources of capital for each. The “about” tab for that visualization includes a statement about “How to Read” the graphic. Such “How to Read” statements recognize that the visual vocabulary of innovative sites may not be familiar enough to make an argument without further explication of methods.

¶ 22

Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0

Figure 9: Relationship between income and life expectancy worldwide from Hans Rosling’s “Gapminder”

Figure 9: Relationship between income and life expectancy worldwide from Hans Rosling’s “Gapminder”

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 Undoubtedly the biggest advocate for the rhetorical power of statistical animations that incorporate interactive features is the Swedish statistician Hans Rosling. Using a tool called Gapminder, he has created an animation of life expectancy at birth and per capita GDP for all countries since 1800 to demonstrate the evolution of world health.16 One can “play” Rosling’s animation in a non-interactive mode to see the story he tells. Color coding differentiates countries in different parts of the world. And if one scrolls over the circles on the chart one can see which country each represents. Circles vary in size depending on the population of the country, and change in size over time in response to population growth, so the reasonably well informed can quickly locate major countries like China, India, and the United States even without mousing over the circles. There is deep layering of information that is easy to interpret, even without an extensive background. In videos where he talks about the data, Rosling shows that the information illustrates a dramatic narrative of the convergence of the world on higher levels of health and wealth, but the point come across perfectly clearly even without verbal accompaniment.17 Rosling draws on an extremely rich data base and readers are able to customize the display of information according to their own interests. One tab allows readers to orient the circles on a map of the world, rather than on two axes of a chart. Another allows readers to choose which country’s data to include or not include in the animation. If one wants to isolate countries from a single continent, or countries that start out a similar size, one can do so. One can also adjust the timeline to focus on narrower periods where crucial changes might be taking place, instead of having to go through the entire time span for “big picture” changes. Because of this option for customization, Rosling’s project both makes an argument that is explicit in the first animation one sees and provides the basis for further exploration by the reader of his or her own interests. While the kind of graphs used by Rosling were developed prior to the web, they posed real challenges of presentation and interpretation in the 2-D format of print. Animation increases their interpretive force dramatically.

¶ 24

Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0

Figure 10: A page from Whitney Trettien’s “Computers, Cut-Ups, and Combinatory Vovelles,” showing trail of pages viewed

Figure 10: A page from Whitney Trettien’s “Computers, Cut-Ups, and Combinatory Vovelles,” showing trail of pages viewed

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 Animation and reader control of the data stream are not the only ways in which digitization affects interpretation. Websites are new enough that there are still opportunities to subvert standard expectations and make readers more attentive to how visual cues structure an argument (in ways that are much less costly than trying to subvert visual cues in print media). A good example is Whitney Trettien’s, “Computers, Cut-Ups, and Combinatory Volvelles: An Archaeology of Text-Generating Mechanisms,”18 which encourages a non-linear reading of her argument about non-linear texts. The front page of the site does not offer a table of contents or obvious sequential path through the material, but it has a 14×21 grid of white squares, which light up and change color either when moused-over or when specific pages of text are clicked. Color coding allows readers to see which sections of the website deal with specific themes, creating a second way of envisioning the argument. Physical proximity of squares and color groupings work together to create a structure to the argument that is as easy to see as it is to read. Interestingly, the idea of color coding in a grid format was presaged in Elizabeth Peabody’s nineteenth-century Universal History: Arranged to Illustrate Bem’s Charts of Chronology.19 Trettien’s experiment with a visual bread-crumb trail makes it possible to reimagine how arguments can be presented in an environment where the reader controls what page to turn to next.

¶ 26

Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0

Figure 11: Six editions of Darwin’s “Origin of Species” viewed simultaneously. Ben Fry’s “The Preservation of Favoured Traces”

Figure 11: Six editions of Darwin’s “Origin of Species” viewed simultaneously. Ben Fry’s “The Preservation of Favoured Traces”

¶ 27

Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0

Figure 12: The word “slave” in slave narratives, from “Wordseer: Exploring Language Use in Slave Narratives,” University of California, Berkeley

Figure 12: The word “slave” in slave narratives, from “Wordseer: Exploring Language Use in Slave Narratives,” University of California, Berkeley

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0 As Peabody’s work shows, it is possible to use color as a visual cue in print texts, but it is generally prohibitively expensive. Online, color is both efficient and cost-free. A superb example of using color to highlight relationships in text is Ben Fry’s concordance of the six editions of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species completed in his lifetime.20 The original text is represented by each sentence being compressed into a single line. The reader can scroll over each line to get a text box of the sentence. The additions in subsequent editions are represented by different colored lines. The colors allow one to quickly grasp, for example, that chapter four was most extensively revised in the third and fifth editions while chapter six was most extensively revised in the fourth edition. Dramatic changes are visible because of tiny lines of color. This same principle is taken up in the Wordseer project at the University of California, Berkeley. They have digitized a corpus of printed slave narratives and compressed each narrative to a single bar of a heat map. One can then search for words across all of the narratives and see how frequently they turn up in each of the paragraphs, represented by lines within each bar.21 Color, brightness, and lines and bars become powerful ways of making interpretive leaps about texts, so long as one has the background knowledge to understand the implications of the visualization.

¶ 29

Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0

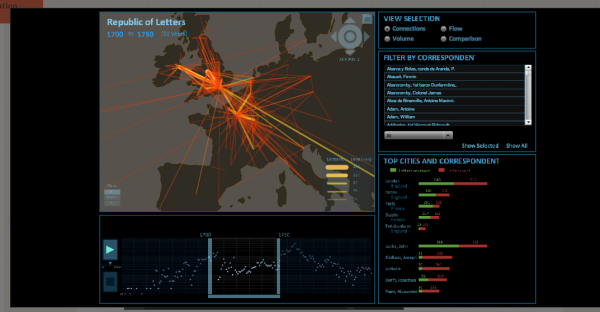

Figure 13: Correspondence network from “Mapping the Republic of Letters,” Stanford University

Figure 13: Correspondence network from “Mapping the Republic of Letters,” Stanford University

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 Much historical writing is implicitly or explicitly about network connections, but historians are less familiar with how social scientists have been visualizing networks than they are with standard statistical visualizations. The Mapping the Republic of Letters project at Stanford University shows how network visualizations can be used in historical work.22 It overlays a networked map of correspondents on the actual map of Europe, with each link in the visualization representing a letter sent between an author at one location and a reader at another. The network described at Mapping the Republic of Letters is personal rather than conceptual, just as the network of boards of directors of railroads mentioned above was. The latter visualization was more complicated because the nodes of the network were not linked to a map, but were a pure visualization of relationships. The online prototype of visualizations of network relationships is Thinkmap’s Visual Thesaurus, which allows readers to move from node to node in pursuit of related concepts.23 Visualizing networks poses several dangers for historians. First of all, network theory of graphs adheres to mathematical principles that have little relation to lived human experiences. In an effective network visualization, the location of nodes is not predetermined, but specified by the nature of the links between them. Remove one source of links from the analysis and the location of nodes may become different. The more complicated the kind of network analysis in the mode of Visual Thesaurus one undertakes, the more likely it is that following any single link trail can quickly get one lost in the thicket of concepts. It is extraordinarily difficult to understand why nodes are in a specific relationship to one another unless one understands the algorithms being used to create the nodes. Thus, network analysis demands the kind of “hermeneutics of data” advocated by Gibbs and Owens in this volume. But even when the concepts and relationships being illustrated are relatively straightforward, the task of visualizing them can prove complicated by the volume of connections being analyzed. The sheer density of nodes can make it hard to single out factors that might interest the reader. In the network visualization of those scholars who make up the “vizosphere,” the leading edge of discussion about the future of visualizations, for example, instead of a clear pattern of lines between sites, there is a barely differentiated blob of circles.24

¶ 31

Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0

Figure 14: Network diagram of the “Vizosphere” by Moritz Stefaner

Figure 14: Network diagram of the “Vizosphere” by Moritz Stefaner

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 Innovative visualizations have entered the mainstream of online user experience in the professions and social sciences. Just as SPSS and SAS and later R were created to enable basic statistical analysis, programs like Gephi have been created to undertake network analysis. In the wake of Tufte’s work, numerous authors now write about information design, though again mostly targeted at a business and journalism audience. Every day, sites like Flowing Data highlight innovative uses of visualization to make new arguments, such as People MovIn, which illustrates migration flows between countries.25 It is clear from these sites that people are still expanding the realm of the possible in visualizing information. Looking over these visualizations, even when they are not explicitly historical, will give historians strategies for making more powerful arguments to complement, and sometimes even substitute for, text. But the task of building those arguments will have to include educating fellow historians about how to interpret visualizations. As noted above, it can be very difficult for the uninitiated historian to intuit relationships between entities in a network analysis when they are put into a visualization scheme. Yet networks are often at the center of questions of greatest interest to historians. To the extent that the difficulties in interpreting innovative visualizations like interactive network diagrams are caused by a simple lack of familiarity with them, they can be overcome by building more such sites. To the extent that they are caused by a lack of background knowledge to understand the cues, creators of such sites will have to learn to build new ways of incorporating that background information as economically in the use of text as possible. In either case, at some point historians will have to accustom themselves to “reading” network diagrams as adeptly as they read maps or scatterplots.

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0 About the author: John Theibault is Director of the South Jersey Center for Digital Humanities @ Stockton College. His training is in the history of Early Modern Europe about which he has written two books.

- ¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0

- The English Emblem Book Project, Pennsylvania State University, http://emblem.libraries.psu.edu/. ↩

- David J. Staley, Computers, Visualization, and History (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2003), 9. ↩

- Daniel Rosenberg and Anthony Grafton, Cartographies of Time: A History of the Timeline (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010). ↩

- Steven Johnson, The Ghost Map (New York: Riverhead, 2006). ↩

- Arthur H. Robinson, “The thematic maps of Charles Joseph Minard,” Imago Mundi, 21 (1967), 95-108. ↩

- One can overstate the degree of that decline. “Social history” was always something of a grab bag term that included non-quantitative approaches. Nevertheless, the relative decline of social history in comparison to cultural history is unmistakable. See Robert B. Townsend, “Decline of the West or Rise of the Rest?,” Perspectives on History, September (2011), http://www.historians.org/perspectives/issues/2011/1109/1109pro1.cfm. ↩

- Edward Tufte, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (Cheshire, CT, 1983), Edward Tufte, Envisioning Information (Cheshire, CT, 1990), Edward Tufte, Visual Explanations (Cheshire, CT, 1997). ↩

- Frederick W. Gibbs and Trevor J. Owens, “The Hermeneutics of Data and Historical Writing,” Writing History in the Digital Age. ↩

- Mark Newman, a physicist at the University of Michigan, gives a good overview of the uses of cartograms and choropleth maps for analyzing the 2008 election returns at the level of state and county voting, at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~mejn/election/2008/. Examples include a simple cartogram of county level results and a choropleth cartogram of the same results. ↩

- Joanna Guldi, “What is the Spatial Turn?” Spatial Humanities, Institute for Enabling Geospatial Scholarship, Scholars’ Lab, University of Virginia, http://spatial.scholarslab.org/spatial-turn/. ↩

- Isao Hashimoto, “1945-1998,” Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBCO), 2003, http://www.ctbto.org/specials/1945-1998-by-isao-hashimoto/. ↩

- Edward Ayers, “Turning towards Place, Space, and Time,” in David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris, eds., The Spatial Humanities: GIS and the Future of Humanities Scholarship (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010) 1-13. ↩

- “Elections, 1840-2008,” Voting America: United States Politics, 1840-2008, Digital Scholarship Lab, University of Richmond, 2010, http://dsl.richmond.edu/voting/elections.html. ↩

- Richard White, Railroaded (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011) and Toral Patel et al., Visualization: Transcontinental Railroad Development, 1879-1893, Spatial History Project, Stanford University, http://www.stanford.edu/group/spatialhistory/cgi-bin/site/viz.php?id=341&project_id=0. ↩

- Shaping the West, Spatial History Project, Stanford University, http://www.stanford.edu/group/spatialhistory/cgi-bin/site/project.php?id=997. ↩

- Hans Rosling, “Wealth and Health of Nations,” Gapminder, http://www.gapminder.org/world/. ↩

- “Hans Rosling shows the best stats you’ve ever seen,” TED Talk, 2006, http://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_shows_the_best_stats_you_ve_ever_seen.html. ↩

- Whitney Trettien, “Computers, Cut-Ups, and Combinatory Volvelles,” http://whitneyannetrettien.com/thesis/. ↩

- Elizabeth Peabody, Universal History: Arranged to Illustrate Bem’s Charts of Chronology (New York, 1859), referred from http://beineckeroom26.library.yale.edu/2011/09/02/visualizing-history/. ↩

- Ben Fry, “On the Origin of Species: The Preservation of Favoured Traces,” http://benfry.com/traces/. ↩

- Wordseer, “Search Slave Narratives,” University of California at Berkeley, http://wordseer.berkeley.edu/slave_narratives/. ↩

- Mapping the Republic of Letters, Stanford University, https://republicofletters.stanford.edu/#maps. ↩

- Thinkmap, Visual Thesaurus, http://www.visualthesaurus.com/. ↩

- Moritz Stefaner, Vizosphere, http://www.visualizing.org/full-screen/29391. ↩

- Nathan Yau, Flowing Data, http://flowingdata.com; PeopleMovin: Migration flows across the world, http://peoplemov.in/. ↩

Comments

Comments are closed

0 Comments on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

0 Comments on paragraph 15

0 Comments on paragraph 16

0 Comments on paragraph 17

0 Comments on paragraph 18

0 Comments on paragraph 19

0 Comments on paragraph 20

0 Comments on paragraph 21

0 Comments on paragraph 22

0 Comments on paragraph 23

0 Comments on paragraph 24

0 Comments on paragraph 25

0 Comments on paragraph 26

0 Comments on paragraph 27

0 Comments on paragraph 28

0 Comments on paragraph 29

0 Comments on paragraph 30

0 Comments on paragraph 31

0 Comments on paragraph 32

0 Comments on paragraph 33

0 Comments on paragraph 34