Historian’s Craft, Memory & Wikipedia (Wolff)

The Historian's Craft, Popular Memory, and Wikipedia (2012 revision)

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 How has the digital revolution transformed the writing of history? If asked, I suspect most historians would point to the tremendous advantages of electronic access to published scholarship and primary sources. In this view, the digital revolution has served primarily to enhance scholarly productivity, much as other once new technologies such as online card catalogues and word processing software facilitated research and writing. Yet as the essays in this volume demonstrate, digital spaces offer platforms for entirely new kinds of research while “digital-first” publishing simultaneously accelerates the propagation of ideas. As Dan Cohen observes, this nascent transformation in the historian’s craft challenges an academic status quo that assumes scholarly success and intellectual credibility stem from a Ph.D. and published monograph. Even as radically new forms of publication emerge, print-first journals and books continue to reign over the profession. No wonder that despite a willingness to explore new media, few historians take the plunge and immerse themselves in the digital world. Concerned that online scholarship will be found wanting by their peers and institutions, most shy away.1 Open source knowledge generated through transparent drafting and review procedures does not yet resonate with the norms of the historical profession, nor does the notion that quality scholarship might be freely available.2 Beyond the ivory tower, however, purportedly authoritative histories proliferate throughout the Internet, accessible to all. And herein lies an important challenge for professional historians as they confront the digital age.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Underlying much of the trepidation with digital-first scholarship may be the realization that on the web, we are not the sole arbiters of what constitutes “history.” Even as academic scholarship (with some exceptions) lies on library shelves or behind electronic subscription paywalls, vast swaths of historical information and analysis can be found readily on the open web. For the experienced scholar, the riches there seem endless. In moments I can choose class material from Documenting the American South (see Figure 1 below), browse the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, and peruse the criminal records of The Old Bailey. I can read about 18th-century funeral broadsides at Common-Place, or download articles from the latest African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter.3 Yet the exponential growth of historical discourse on the internet draws not upon the labors of professional historians, but rather the wider public that edits entries on Wikipedia, contributes to genealogical discussions on Ancestry.com, posts photos of historic sites to Flickr.com, and invokes the Founding Fathers or scripture in the comment pages of the Washington Post.

¶ 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0

Figure 1: Click to view Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.

Figure 1: Click to view Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 People with little or no formal training in the discipline have embraced the writing of history on the web, which raises the question, whose histories will prove authoritative in the digital age? Since the professionalization of history in the last decades of the 19th-century, college and university professors have worn the mantle of authority. Through creation of professional associations such as the American Historical Association (founded 1884) and editorial control of academic journals and book presses, they have determined which narratives meet their standards of scholarly rigor.4 At first the emergence of the digital age did little to dilute the authority of disciplinary experts in history but that has begun to change. Although Dan Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig rightly observed that, “The Internet allows historians to speak to vastly more people in widely dispersed places,” it can just as easily be said that the Internet allows vastly more people to speak about history without professional historians.5 The popular understanding of the past differs greatly from that of academic historians; it often reflects an effort to muster the past in service of a particular worldview. As such it may tell us as much about memory – how events are remembered – as it does history.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Ordinarily historians see history and memory as distinct ways of understanding the past, the former governed by professional imperatives, the latter by cultural and familial expectations. David Blight summarizes this distinction as follows: “History – what trained historians do – is a reasoned reconstruction of the past rooted in research; critical and skeptical of human motive and action…. Memory, however, is often treated as a sacred set of potentially absolute meanings and stories, possessed as the heritage or identity of a community. Memory is often owned; history, interpreted. Memory is passed down through generations; history is revised.”6 Writing history in the digital age will force professional historians to share a space (i.e., the Internet) with others whose narratives draw upon the “sacred set of potentially absolute meanings” that characterize popular memory. Nowhere is this characteristic of the web more apparent than in Wikipedia, which for good or ill provides more historical information to the public than any other site on the web. Type any historical topic into the search engine of your choice; chances are excellent that the first hit will be Wikipedia. Its extensive entries demonstrate the ways in which popular understandings shape digital narratives about the past.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Why explore writing history through Wikipedia? Simply put, because it allows any reader to peel away layers of narrative to explore how entries have changed over time, juxtaposing revisions for comparison. In keeping with its self-fashioned identity as a community of writers, Wikipedia also maintains discussion pages for each entry that permit even the casual visitor – as well as the scholar bent on digital history – to follow the give and take between different contributors. In short, Wikipedia invites readers to peer behind the curtain and if interested take a place at the controls. It is this open-source quality that has troubled many observers, who question the accuracy of its entries and/or deny that it has any utility as a reference source for students and the wider public. Rather than discuss its accuracy, however, I wish to explore the process by which Wikipedia contributors craft entries about the past. Despite protestations that its entries may not serve as either a “soapbox” or “memorial site,” Wikipedia is not simply an online encyclopedia.7 Its historical entries serve as virtual “sites of memory” (to borrow from Pierre Nora), places at which people attempt to codify the meaning of past events 8 Moreover, as they discuss and debate the language used to narrate the past, Wikipedia contributors may strive for a “neutral point of view” (NPOV) but in practice they judge new entries and revisions via a moral economy of crowdsourcing.9

¶ 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

Figure 2: Click to view Wikipedia entry for “Origins of the American Civil War.”

Figure 2: Click to view Wikipedia entry for “Origins of the American Civil War.”

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 How does Wikipedia depict past events? How do contributors resolve debates about history? What happens when popular understandings (memory) clash with academic discourse (history)? To answer these questions I traced a single entry for the “Origins of the American Civil War” (OACW) beginning with its first appearance in December 2003, when the anonymous user 172posted a dense, 9700-word essay, accompanied by two images. Since then, more than 900 other users (some of them automated) have updated the page,10 which now consists of roughly 19,000 words, fourteen images, four maps, as well as copious notes and bibliography. Because debates about the war’s origins have often served as proxies for other struggles, such as the 20th-century Civil Rights movement, the OACW seemed likely to show traces of contestation. Depending upon region and background, as a sizeable literature demonstrates, the popular understanding of the American Civil War varies tremendously.11 I paid particular attention to skirmishes in the OACW’s discussion and history pages (see Figure 3 below). Most editorial changes elicited no controversy whatsoever; they either added new information or tackled the perennial problems of organization that plague longer Wikipedia entries. I also ignored minor acts of vandalism. For example, for nearly five days in 2004, the phrase “Michael Cox is the coolest kid at CMS” appeared in the OACW; perhaps for those days he was.12 Excepting these pages, considerable discussion about the “Origins of the American Civil War” occurred behind the scenes as contributors challenged one another over terminology, imagery, and context.

¶ 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

Figure 3: Click to view enlarged image of “Discussion” and “View History” tabs in Wikipedia.

Figure 3: Click to view enlarged image of “Discussion” and “View History” tabs in Wikipedia.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 Wikipedia currently provides a plausible if somewhat rambling essay on the Origins of the American Civil War. It opens with a statement with which many academics will agree: “The main explanation for the origins of the American Civil War is slavery, especially Southern anger at the attempts by Northern antislavery political forces to block the expansion of slavery into the western territories. Southern slave owners held that such a restriction on slavery would violate the principle of states’ rights.”13 On this essential point the OACW shares the broad consensus in the historical profession. User 172’s narrative of the events leading up to the American Civil War resembles that of many American history textbooks; it covers the rise of the Republican party, Kansas-Nebraska Act, “Bleeding Kansas,” and the collapse of the Whig party as a national alternative to the Democrats. It further places that narrative within the context of a significant historiographic divide between scholars who have viewed the Civil War as irrepressible (i.e., the inevitable consequence of the regional differentiation between an agrarian, slave-labor South, and an increasingly industrial, free-labor North) and those who have argued that the conflict was repressible (i.e., the result of blundering politicians and/or reckless agitators in both regions). To be sure, the original narrative did not address events that professional Civil War historians today see as essential to our understanding of secession and the outbreak of hostilities, such as the Compromise of 1850, Fugitive Slave Act, and John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry. User 172 relied upon much dated historical works, which explains the narrow emphasis chronologically (the 1850s) and thematically (politics).14

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Beyond this, the OACW offers an unruly congeries of information reflecting its crowdsourced roots. It’s not just that every Wikipedian is his or her own historian, but that for each, the past possesses different meanings. User 172’s narrative strongly suggested that white Southerners bore more responsibility for the outbreak of war than their Northern counterparts. The “vitriolic response” of the “Reactionary South” to northern concerns about slavery in the Western territories exacerbated sectional tensions. Southerners, “increasingly committed to a way of life that much of the rest of the nation considered obsolete,” therefore responded to the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 by seceding from the Union.15 In January 2005, a contributor with the evocative name Rangerdude challenged “anti-southern biases” in the OACW, objecting to the header “The Reactionary South” as “pejorative” and deleting a reference to the South’s “hysterical racism.”16 Underlying Rangerdude’s criticisms lay a preoccupation with the OACW’s depiction of non-slaveholding whites in the South as racist: “The term is a modern one and is not neutral for a historical article.”17 Not surprisingly, Rangerdude’s editorial changes provoked a response several hours later from 172 who insisted that the underlying causes of the Civil War could not be addressed without discussing racism. “To claim that all references to racism should be removed from the article is patently absurd. It would leave us with no way to address how white people came to believe that Africans should be kept in bondage. That’s why the relationship between slavery and racism has inspired a rich tradition in scholarly literature…”18 In an “edit war,” the two contributors fought back and forth, taking turns deleting the other’s revisions and substituting his own text. At one point, Rangerdude exclaimed, “Please do not revert edits because they remove bias that you happen to like.”19 User 172 asserted the importance of authoritative secondary sources, while Rangerdude challenged 172 through demands for neutrality. Perhaps because both invoked the moral economy of Wikipedia, if in different ways, revisions to OACW sought a middle ground. “The Reactionary South” gave way to “The Southern Response.” A reference to southern whites so poor they “resorted at times to eating clay” disappeared. References to Southern racism, supported by 172’s references to secondary sources, remained.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 But what happened when one person’s interpretation clashed with the collective narrative? In August 2004, user H2O insisted that OACW include African American slaveholders in its description of the antebellum South.20 “The article,” H2O complained, “implies that [slavery] was about the rich white people suppressing the poor black people, when it was really about the powerful (white or black) using the powerless (white or black) for their own gain, as evidenced by the fact that there were free black slaveowners who took advantage of the system as well.” This is of course a nonsensical position as there were no instances of powerful blacks owning white slaves. For H2O, slavery was simply an exploitative economic system in which white and black participated equally according to their ability. That all slaves were of African descent H2O must have seen as incidental. Elsewhere s/he makes the claim that slaveholders “treated their slaves kindly, and wanted to see an end to slavery, and believed that it eventually would die out, but did not see a simple way to end the practice.”21 Another contributor proposed that the OACW be re-written to reflect that Northern aggression led to hostilities, driven by people “wholly opposed to the regular order of living and more into experimentation, the counter-culture.”22 Neither of these proposals led to changes in the OACW because other contributors judged them baseless. In other words, they failed to meet the community’s standard for authoritative information. These examples, from both the OACW page and talk history, suggest that the Wikipedia community does effectively gauge basic historical knowledge, and can exclude claims that lack a factual basis.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Authoritativeness in Wikipedia, however, is not simply an imperfect version of scholarly authority. In other words, although it is tempting to see Wikipedia as a space in which the expertise of professional historians is not yet (or not always) recognized, the popular understanding of the past that informs Wikipedia’s moral economy has never accepted Ph.D. academics as definitive experts. Of course some contributors do acknowledge the influence of professional scholarship. When challenged by Rangerdude to defend the argument that Southern society entwined slavery and racism, User 172 cited a battery of prize-winning scholars — Oscar and Mary Handlin, Winthrop Jordan, David Brion Davis, Peter Wood, and Edmund Morgan.23 Others reject scholarly expertise altogether, positing that only original sources can reveal true history. For example, user 138.32.32.166 lambasted other contributors for their “repugnant bias.” By this, s/he meant that instead of presenting just the facts, they “editorialized.” First-person perspectives are authoritative, 138.32.32.166 seemed to say, but everything else is opinion. “Remember in you[r] search for history, do read memoirs, diaries and other accounts. Old newspapers articles are always interesting. You can always corroborate the memoirs etc… for accuracy against accounted for events.” For this person, history can only be accurate if it chronicles the past in the words of those who experienced it.24 Across this spectrum contributors share a belief that known facts form the foundation of historical narrative. A willingness to see professional scholarship as a source of factual information separates user 172 from 138.22.32.166 but not even 172 acknowledges that historians interpret past events. Intriguingly, although OACW contributors accept slavery as a cause of the Civil War, and racism as a fundamental aspect of antebellum Southern society, later in this volume Martha Saxton demonstrates that Wikipedia editors consistently obscure American women’s history through “suppression, exclusion, and marginalization.” As they argue, American exceptionalism — the desire for a unitary, triumphalist historical narrative — frames the worldview that many contributors bring to Wikipedia.25

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 Although impossible to specify for any one entry, the demographics of Wikipedia contributors must also play a role in shaping their perspectives on the past. According to its own research, Wikipedia contributors are 26 years old on average. Roughly half hold a bachelor’s or more advanced degree. Surprisingly, 34 percent have completed high school only, and 11 percent not even that.26 If the profile of OACW contributors resembles this overall picture, most have studied history – in high school or college — but few will have studied it in depth. Perhaps this explains the stunning omission of Edward Ayers’ prize-winning In the Presence of Mine Enemies, and its companion website, The Valley of the Shadow from the OACW.27

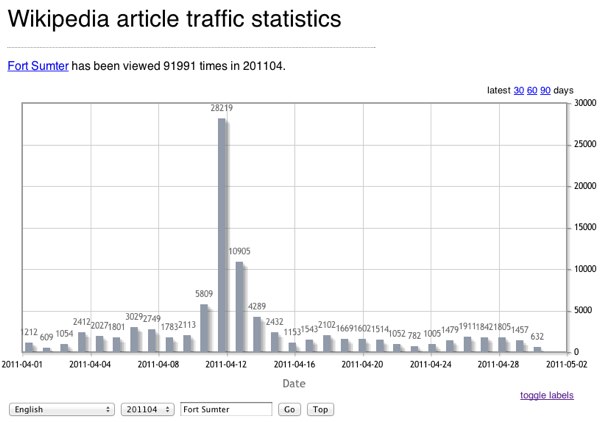

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 If, according to Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, “millions of Americans regularly document, preserve, research, narrate, discuss, and study the past,” it should not be surprising that they are drawn to Wikipedia.28 More than just an encyclopedia, Wikipedia serves as a people’s museum of knowledge, a living repository of all that matters where the exhibits are written by ordinary folk with nary an academic historian in sight. On the 150th anniversary of the firing on Fort Sumter, South Carolina (the event that began the American Civil War), more than 28,000 people visited the fort’s Wikipedia entry (see Figure 4 below). In 2011, when presidential aspirant Sarah Palin provided her own take on Paul Revere’s famous ride, people turned to Wikipedia in droves – peaking at 140,000 in a single day.29

¶ 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0

Figure 4: Click to view Wikipedia traffic for Fort Sumter in April 2011, with visualization by user Henrik.

Figure 4: Click to view Wikipedia traffic for Fort Sumter in April 2011, with visualization by user Henrik.

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 As the digital revolution spreads popular historical narratives, academic and public historians have an unprecedented opportunity to make our expertise available and relevant to an audience that whatever its assumptions possesses a deep, abiding investment in the importance of the past. This is not a plea for all Ph.D. scholars to rush out and edit Wikipedia pages – far from it – but it is a call to greater engagement with those digital spaces that “document, preserve, research, narrate, discuss, and study the past.” That engagement can take many forms but must begin with an acknowledgement that popular audiences understand and have always understood history without the scholarly norms familiar to professional historians. Digital technology may transform the production and performance of historical narratives but it will not necessarily change the relationship between the public and the academy. That said, open discussions of NPOV, targeted “wikiblitzes” (such as the one described in this volume by Shawn Graham),30 and sustained efforts to better integrate academic insight into popular narratives (see again Saxton), can all be part of a larger strategy to reconcile history and memory. Indeed, this is essential because the momentum of the digital age can only further blur the line between scholarly and popular narratives of the past, a line first drawn in the late 19th century with the professionalization of history. Before that moment published histories were but one form of memory. In the 21st century the discipline of history seems likely to come full circle as all history and memory become digital. This does not mean that monuments, museums, historical re-enactments, and print scholarship will disappear, but rather the normative form of access to the past will be electronic and that line between history and memory difficult to discern.

¶ 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

About the author: Robert S. Wolff is Professor of History at Central Connecticut State University.

- ¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0

- Dan Cohen, “The Ivory Tower and the Open Web: Introduction: Burritos, Browsers, and Books (Draft).” Dan Cohen’s Digital Humanities Blog, 26 July 2011. http://www.dancohen.org/2011/07/26/the-ivory-tower-and-the-open-web-introduction-burritos-browsers-and-books-draft/; Robert Townsend, “How Is New Media Reshaping the Work of Historians?” AHA Perspectives (November 2010), http://www.historians.org/perspectives/issues/2010/1011/1011pro2.cfm. ↩

- In addition to this volume, see for example Kathleen Fitzpatrick, Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy (New York: NYU Press, 2011), which first emerged online at http://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/mcpress/plannedobsolescence/. ↩

- Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library, http://docsouth.unc.edu/; Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin Library, http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/; The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674-1913, University of Sheffield, http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/; Joanne van der Woude, “Puritan Scrabble: Games of Grief in Early New England,” Common-Place 11, no. 4 (July 2011), http://www.common-place.org/vol-11/no-04/van-der-woude/; African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, http://www.diaspora.uiuc.edu/newsletter.html. ↩

- American Historical Association, http://www.historians.org; Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: the “Objectivity Question” and the American Historical Profession (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993). ↩

- Daniel J. Cohen and Roy Rozenzweig, Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 5. ↩

- David W. Blight, Beyond the Battlefield: Race, Memory, and the American Civil War (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2002), 2. ↩

- See Roy Rosenzweig, “Wikipedia: Can History Be Open Source?,” Journal of American History 93, no. 1 (June 2006): 117-46; “Wikipedia: Key policies and guidelines,” and “Wikipedia: What Wikipedia is not,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Key_policies_and_guidelines and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:What_Wikipedia_is_not. ↩

- Pierre Nora, “History and Memory; Lex Lieux de Mémoires,” Representations 26 (Spring 1989): 7-24. ↩

- “Wikipedia: Neutral point of view,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Neutral_point_of_view. By moral economy I mean a set of normative beliefs and expectations collectively held. ↩

- For more on automated editing, see R. Stuart Geiger, “The Lives of Bots,” in Geert Lovink, and Nathaniel Tkacz, eds., Critical Point of View: A Wikipedia Reader, Institute of Network Cultures Reader 7 (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011), 78-93. ↩

- This particular topic lies close to my own expertise – I teach a graduate course on Civil War and Reconstruction – but is also the subject of many volumes. See, for example, Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997); David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001); David W. Blight, ed., Beyond the Battlefield (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2002); Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause and the Emergence of the New South, 1865-1913 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988). ↩

- OACW, 16:39, 12 May 2004, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Origins_of_the_American_Civil_War&oldid=3550913. With so many citations to the same Wikipedia page, I developed this shortened form for use in the notes. Unless otherwise noted, access to all Wikipedia URLs were verified in March 2012. ↩

- OACW, 23:20, 11 August 2011, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Origins_of_the_American_Civil_War&oldid=444350362. This is a permanent link to the page current when this chapter was completed. ↩

- OACW, 9:12, 20 December 2003, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Origins_of_the_American_Civil_War&oldid=2005512. ↩

- OACW, 11:39, 21 December 2003, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Origins_of_the_American_Civil_War&oldid=2014509. ↩

- Wikipedia user Rangerdude, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=User:Rangerdude&action=history. ↩

- Talk:OACW, 07:07, 8 January 2005, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Talk:Origins_of_the_American_Civil_War&diff=prev&oldid=9198574. Please note that Talk:OACW citations are references to the OACW discussion page, not the Wikipedia entry itself. ↩

- Talk:OACW, 12:49, 8 January 2005, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Talk:Origins_of_the_American_Civil_War&diff=next&oldid=9201516. ↩

- OACW, 6:48, 8 January 2005, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Origins_of_the_American_Civil_War&diff=next&oldid=9197400. ↩

- Wikipedia user H20, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=User:H2O&action=history. ↩

- OACW, 7:43, 16 August 2004, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Origins_of_the_American_Civil_War&oldid=5234557; Talk:OACW, 9:17, 16 August 2004, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Talk:Origins_of_the_American_Civil_War&diff=next&oldid=5235613. ↩

- Talk:OACW, 2:51, 23 December 2008, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Talk:Origins_of_the_American_Civil_War&diff=prev&oldid=259648581. ↩

- OACW, 12:49, 8 January 2005, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Talk:Origins_of_the_American_Civil_War&oldid=9201556. ↩

- Talk:OACW, 08:34, 28 June 2010, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Talk:Origins_of_the_American_Civil_War&oldid=370560458. ↩

- Martha Saxton, “Wikipedia and Women’s History,” in Writing History in the Digital Age. ↩

- Ruediger Glott, Philipp Schmidt, and Rishab Ghosh, Wikipedia Survey — Overview of Results. Collaborative Creativity Group, UNU-MERIT, United Nations University, March 2010. The data also show that the vast majority are men; fewer than 13 percent are women. See http://www.wikipediastudy.org/. ↩

- Edward L. Ayers, In the Presence of Mine Enemies: War in the Heart of America, 1859-1863 (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2003); Ayers, “The Valley of the Shadow: Two Communities in the American Civil War,” Virginia Center for Digital History and the University of Virginia Libraries, 1997-2003, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/. ↩

- Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 24. ↩

- Chris Beneke, “Revere, Revisited,” The Historical Society; A Blog Devoted to History for the Academy and Beyond, June 13, 2011, http://histsociety.blogspot.com/2011/06/revere-revisited.html; for stats, see User: Henrik (a Wikpedia admin), “Wikipedia Article Traffic Statistics,” http://stats.grok.se/en/201104/Fort Sumter. ↩

- Shawn Graham, “The Wikiblitz: A Wikipedia Editing Assignment in a First Year Undergraduate Class,” in Writing History in the Digital Age. ↩

Comments

Comments are closed

0 Comments on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

0 Comments on paragraph 15

0 Comments on paragraph 16

0 Comments on paragraph 17

0 Comments on paragraph 18

0 Comments on paragraph 19