Writing Chicana/o History (Rosales Castañeda) Fall 2011

Writing Chicana/o History with the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project (Fall 2011 version)

Fig. 1: Student contingent from UW MEChA at a Rally Before an Anti-War March, c. 1971 (Image Courtesy of the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, UW)

Fig. 1: Student contingent from UW MEChA at a Rally Before an Anti-War March, c. 1971 (Image Courtesy of the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, UW)

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 In 2005, coming off the initial release of the newly minted Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project,1 a group of undergraduate students met with University of Washington (UW) History Professor, Dr. Jim Gregory and UW PhD Candidate, Trevor Griffey, to initiate dialogue on expanding the Civil Rights Project’s reach to include the local ethnic Mexican and Latino communities in Seattle. This preliminary meeting would result in the creation of the largest archive documenting the Chicana/o Movement2 outside of the traditional confines of the American Southwest. Nationwide, this would reverberate throughout academic circles as a model for utilizing undergraduate students in producing academic material used in educating students at both the k-12 and college levels.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 From the onset, the “Chicana/o Movement in Washington State History Project” (hereafter referred to as the “Chicana/o Movement Project”) was intended as a point of departure; an exploration of a local narrative that had long been relegated to obscure, unpublished materials and oral histories passed down from one generation to the next. For many in the Latino community in Seattle and the Pacific Northwest in general, the thirst for knowledge was tempered by a sense of isolation from the Ethnic Mexican and Latino cultural hubs in the southwest and east coast of the United States as well as a sense of historical omission in regional historical narratives. The need for addressing this dual marginalization from southwest-centric Chicana/o scholarship as well as exclusion from Pacific Northwest history textbooks proved to be the impetus for initiating the Chicana/o Movement Project research unit.

¶ 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3 1

Latinos in the Pacific Northwest

Interest in recording the Chicana/o activist history at the University of Washington (UW) emerged from a contingent of first year students as early as 2002. These students, most arriving from high schools in Eastern Washington, and some from the Seattle area came together as the newly minted organizational class that formed the leadership of the UW Chapter of El Movimiento Estudiantil Chicana/o de Aztlan (The Student Movement of Aztlan)3 or “MEChA.” To many, this was the first time they had come together with other like-minded youth to organize around questions pertaining to educational access, economic justice, as well as civil and human rights. The previous year’s leadership had graduated the summer before this new group arrived. Their departure left an organizational vacuum that prompted this younger class to take over the reins of the leadership in order to ensure that MEChA would continue as it had since the fall of 1968.4

¶ 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

Fig. 2: MEChA de UW group photo in front of Suzzallo Library at the University of Washington on April 5, 2006. The Author is in the first row, second from right. (Image from Author’s Personal Photo Collection)

Fig. 2: MEChA de UW group photo in front of Suzzallo Library at the University of Washington on April 5, 2006. The Author is in the first row, second from right. (Image from Author’s Personal Photo Collection)

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Among the initiatives the students put forth were the use of educational meetings which served to share skills and knowledge as well as train themselves and subsequent classes in organizing strategies and tactics. They understood that there was a specific relation between themselves and the space they inhabited as Latinos in the Pacific Northwest. Far removed from the urban cultural hubs in the southwest, yet very much a part of a cultural Diaspora that adapted to its new surroundings, they imagined a new way of being and collaborating with other communities of color that represented a smaller portion of the total population, in contrast to places like Southern California, Texas, Florida, and New York.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 1 The first real encounter with this Ethnic Mexican and Latino Historical narrative in the Pacific Northwest came through a class instructed by Northwest Historian and Mexican ‘Bracero’ scholar, Dr. Erasmo Gamboa.5 Though the class served in introducing material that many students had not encountered in Washington State History textbooks, the material was still relegated to the rural experience. The urban narrative existed, as many later found out, in a patchwork collection of journal articles, Masters Theses, personal document collections, newsletters, organizational papers and unpublished lithographs that remained out of the reach for people in the community not privileged enough to be enrolled at the University of Washington. As a means of addressing this issue, the UW MEChA Chapter undertook the task of centralizing and consolidating material pertinent to the history of Chicano and Latino students at the university.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 As this project was underway, the leadership of MEChA de UW, of which I was the Chapter Co-Chair, received an e-mail link from an alumnus who was now a graduate student at California State University, Northridge. While doing a Google search, he stumbled upon former UW Activist, Jeremy Simer’s article, “La Raza Comes to Campus,”6 published as a series of papers from Dr. Jim Gregory’s Independent Research Seminar at UW. The discovery of this article profoundly impacted how MEChA viewed the utilization of digital media in collecting this history. As the year progressed, I was successful in acquiring a research fellowship for the upcoming 2005-2006 academic year, as I argued that the project would “aid in incorporating scholarly work from the Pacific Northwest into the study of Latinos on the west coast, enhancing the already existing historical narrative.”7 In addition, I was fortunate enough to receive a second fellowship from the UW’s Center for Labor Studies which was presented at the center’s annual awards ceremony, where I finally met Dr. Gregory in person. As a consequence of having a sizeable class that entered in 2002, we had a group of graduating students looking to initiate Senior Thesis projects. We now had the undergraduate research contingent as well as the resources to finally unearth our collective vision.

¶ 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0

Urban Activism in Seattle

The project was organized with the intent of examining the local movement’s unique character, in relation to its spatial confines in a city long known for its vibrant social movement history. Unlike the cultural nationalist current prevalent in cities such as Los Angeles, San Diego, and many other communities along the southwest at that time, activity in Seattle mirrored the third world and internationalist tendencies witnessed in the San Francisco Bay area. Furthermore, unlike the southwest, activity in Seattle and other towns and cities in Washington State differed as there was no significant record of social and political mobilization within the Ethnic Mexican and Latino community.8

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 Upon preliminary reading of primary sources, it was evident that the original plan would have to be placed on hold. A survey of this historical narrative from its early history in rural farm worker activism to later urban youth, social, cultural and political movements had yet to be written. As would be the case, many original writings had been segmented and fragmented, written in four-to-five year increments. Furthermore, much of this story lay in a tapestry of rare documents, newspaper articles, personal writings and random ephemera that had not been seen by activists and community members since at least the early 1970s. This reality forced us to change our tactics and utilize a three pronged approach with some undergrad researchers conducting oral history interviews, others digging into archival material and fishing out newspaper articles, and yet others creating written material and digitizing rare, tattered organizational documents that sat in MEChA de UW’s file cabinet for decades. As such, we instead opted to weave these writings on farm labor unionization, student strikes, urban and rural activism and literary and artistic movements into one solid historical survey that encompassed a 15 year period from 1965 to 1980.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 With the project finally taking form, interest in the research slowly surfaced. Nationwide, polemic debate around immigration seeped into mainstream parlance. Early in the spring of 2005, a group calling itself the “Minuteman Project” began conducting armed patrols of the U.S.-Mexico border under the pretext that the borders were porous and susceptible to “terrorist organizations,” a reflection of the anti-Muslim and as can be surmised, anti-immigrant hysteria seen in the post 9/11 era. Soon thereafter, this staunchly nativist group began patrolling the northern border, perhaps most visibly in Washington State’s northern counties. This right-wing anti-immigrant formation in turn influenced conservative policy makers whom by late December of 2005 passed House Resolution 44379 (more commonly referred to as the ‘Sensenbrenner Bill,’ the name of the legislation’s primary sponsor, Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin).

¶ 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0

Fig. 3: A Flyer for the May Day 2006 March in Seattle. The march drew an estimated 50-65,000 participants. (Image courtesy of El Comite Pro-Reforma Migratoria Y Justicia Social)

Fig. 3: A Flyer for the May Day 2006 March in Seattle. The march drew an estimated 50-65,000 participants. (Image courtesy of El Comite Pro-Reforma Migratoria Y Justicia Social)

¶ 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

Fig. 4: Seattle Police Officers close major streets as marchers make their way through Downtown Seattle on May 1, 2006 (Image from Author’s Personal Collection)

Fig. 4: Seattle Police Officers close major streets as marchers make their way through Downtown Seattle on May 1, 2006 (Image from Author’s Personal Collection)

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 In response to this highly controversial, draconian legislation, immigrants and their allies took to the streets en masse in the spring of 2006 for what was perhaps the largest wave of mass demonstrations in a generation in the U.S. In the Seattle area, Ethnic Mexican and Latino immigrants came out in force as never before. In a meeting, Dr. Gregory related that as a result of recent happenings, subsequent search engine queries for information on the subject led to our rudimentary project site (which only had a few pages, most under construction). We were still a few months from completion and yet the need to tie in events from the present day to our narrative was a reflection of the fact that regionally, the narrative was still being written. Nevertheless, in spite of lacking an accessible established historical narrative infrastructure, the demand for this information was apparent. This course of events provided the impulse for increased interest in regional scholarship in the Pacific Northwest.

¶ 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0

Teaching and Researching History in the Present Day

Since 2005, scholarship on Latinos in the Pacific Northwest has resurfaced from its dormant stage from the last flurry of activity in the early-to-mid 1990s. Of note, one of the most recent collection of essays, “Memory, Community and Activism: Mexican migration and labor in the Pacific Northwest” edited by Jerry García and Gilberto Garcia,10 expands this examination of Ethnic Mexican communities in the Pacific Northwest by including cross-cultural collaboration in labor, the cultural significance of Art and public space in the Pacific Northwest, the role of the Church in community activism and most critical, the major role that gender has played in community organizing in the Pacific Northwest. In addition, Garcia (Jerry) also published a book documenting the presence of the community in Quincy, Washington, entitled, “Mexicanos in North Central Washington.”11

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 1 Along with the previously noted examples, there are also a few articles, theses and Ph.D. dissertations that focus on Chicana and Chicano Experiences in the Pacific Northwest that have recently been produced. Aside from the Chicana/o Movement Project at UW, other research projects recently produced and or transferred to digital format include, the Chicano/Latino Archive hosted by The Evergreen State College Library, and the Columbia River Basin Ethnic History Archive out of WSU Vancouver.12 The proliferation of these new sources within the last few years in turn complemented and helped strengthen the Chicana/o Movement History Project’s visibility. It is in this way, that collective amnesia within Washington State History textbooks and textbooks on Chicana/o History are challenged to include the history of the community in the north. In effect, the literary definition of “borderlands” take on different meaning as the experience at the U.S.-Canadian Border region becomes a part of the larger historical narrative, augmented by the use of digital media to teach this unique history.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 It has been over five years since the Chicana/o Movement in Washington State History Project was officially unveiled in August of 2006. Three years later, a sister project, the Farm Workers in Washington State History Project went live in September 2009. Much like its predecessor, it followed the same pattern and worked to acknowledge the history of union organizing for Washington’s most marginalized, most forgotten farm laborer population. Besides influencing additional research projects, the Chicana/o Movement History Project has also been used as required reading for U.S. History classes at the University of Washington, Whitman College (a liberal arts college in Walla Walla, Washington), Washington State University, Western Washington University, and others institutions, namely, the University of California at Los Angeles and the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, among others.

¶ 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0

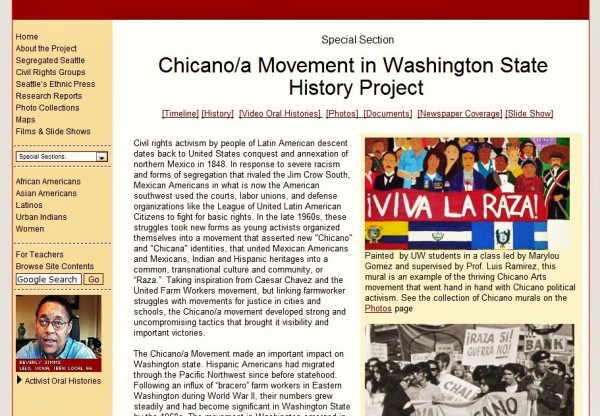

Fig. 5: Screen Capture of the Chicana/o Movement in Washington State History Project Home Page (Courtesy of the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project)

Fig. 5: Screen Capture of the Chicana/o Movement in Washington State History Project Home Page (Courtesy of the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project)

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 The project, in addition to the larger Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project has also been featured on the American Historical Association’s “Perspectives” publication, various Oral History and Diversity oriented publications, and newspapers ranging from the Seattle Times and Seattle Post-Intelligencer, to the New York Times, USA Today and the local National Public Radio Affiliate, KBCS.13 The research has also been mentioned on the Civil Rights Digital Library,14 as well as the site “teachinghistory.org.” 15 Likewise, the local Public Broadcasting System (PBS) Affiliate, KCTS Seattle, Produced a brief documentary detailing the role of the first class of Latino students at the University of Washington, entitled “Students of Change: Los del ’68,”16 which used much of the background material researched by the Chicana/o Movement History Project.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 Perhaps most profoundly impactful to many of us, who produced the project, are comments and e-mail messages from community members who have stumbled upon the project or were referred to the site by a teacher or professor. For many, it was their first introduction to the local history of the Latino community in Washington State. They validated not only the struggle in producing the material, but also the reason for why it matters and for why it merits further scholarship. To this day, the project is among one of the first nationwide to accomplish what it has done in fusing public history and academic production. Perhaps even more remarkable as it allowed undergraduate students the space to produce information that has drastically changed the way that history, and in particular, Chicana/o Scholarship is taught in the State of Washington.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 About the author: Oscar is an independent scholar/activist/writer/organizer based out of Seattle, Washington. He became involved in youth organizing with the University of Washington MEChA Chapter and the Student Labor Action Project while a student at the University of Washington and soon thereafter, used his knowledge to write about social justice issues. He has contributed writing and has been a researcher for the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, and was previously an editor and contributor for HistoryLink.org, focusing on “Hispanic-American History” in Washington State. Presently he also serves as Communications Director for El Comite Pro-Reforma Migratoria Y Justicia Social, an immigrant rights and social justice organization based in Seattle. His writings mostly center on labor history, social movements, immigrant rights and educational access, among other topics.

- ¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 1

- According to its website, “The Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project is based at the University of Washington. It represents a unique collaboration involving community groups, UW faculty, and both undergraduate and graduate students. Funding for the project has been provided by the Simpson Center for the Humanities, the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, the Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest, and the following University of Washington offices: the Office of Undergraduate Education, the College of Arts and Sciences, and the Office of the Provost. In addition we gratefully acknowledge support from 4Culture/King County Lodging Tax Fund.” The site has over 14 special sections documenting the history of Seattle’s labor and civil rights movements, ranging from the Seattle General Strike of 1919, to documentation of the United Farm Workers Union’s Fair Trade Apples Campaign of the early 2000s. “About the Project” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project <http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/about.htm> ↩

- The “Chicano Movement” in the United States was at its essence, the rejection of assimilation into the larger dominant culture in the U.S. that sought to erase all semblance of cultural distinction (e.g. customs, language, music, ancestral knowledge) while simultaneously keeping the community in a state of second-hand citizenship that kept many locked in a cyclical poverty, disempowerment, and racism that was commonplace for many communities of color in the United States prior to the formation of the Civil Rights Movement. In the words of Jorge Mariscal, “The elaboration of a radicalized collective agency for ethnic Mexicans in the United States was in itself a major accomplishment. Equally important were the Chicano/a critique of naïve and uncritical patriotism, the exposing of the imperial foundations of U.S. foreign policy, and the Chicana rejection of both subtle patriarchal and openly sexist practices. As the Black Civil Rights Movement had done in the South and urban centers in the North, Chicano/a militancy exposed the legacy of white supremacy and the history of economic exploitation in the Southwest.” George Mariscal, Brown Eyed Children of the Sun: Lessons from the Chicano Movement, 1965-1975, (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2005), 250. ↩

- MEChA is a student organization that has over 400 loosely affiliated chapters throughout the United States. It is one of longest running student-led organization in the country, tracing its roots to a conference at University of California at Santa Barbara in April of 1969. This conference which served in producing a master plan for creating Chicana/o Studies and Education programs also served the purpose of uniting the many activist student organizations, among them the United Mexican American Students (UMAS), the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO), the Mexican American Student Association (MASA), the Mexican American Student Confederation (MASC), and others, under one national organizational banner. In addition to issues of access to higher education, some of the concerns that MEChA initially mobilizing around were opposition to the war in Viet Nam and Southeast Asia, cyclical violence and police brutality, poverty in Ethnic Mexican and Latino barrios and neighborhoods, institutional neglect in the schools, and lack of culturally competent educators and administrators. Similarly, it was a movement that like the Black Power Movement embraced not only pride in their own culture, but also acknowledged their Amerindian Mesoamerican roots. This was perhaps the most noticeable cultural marker visible in the literature and visual arts of this period. ↩

- In Washington State, the emergence of a youth movement first took root in rural Central Washington’s Yakima Valley with the emergent farm worker movement in 1966 and 1967. This however was amplified when Black students at the University of Washington united under the Black Student Union (BSU) occupied the UW Administration building on May 20, 1968 demanding immediate action in the establishment of a Black Studies Program, as well as the recruitment of students of color and economically disadvantaged white students. In the summer of 1968, these efforts led to the recruitment of the largest class of incoming Ethnic Mexican and Latino students to the university. This contingent, aided by the UW BSU, formed the first Mexican American youth organization in Washington State, the United Mexican American Students (UMAS). As participants in a conference at UC Santa Barbara in the spring of 1969, they agreed to consolidate under the national student structure, changing its name and image to MEChA, the name the organization still carries today. In recent years, MEChA has continued the work initiated by the first class that arrived in 1968, with participation in the WTO Demonstration in Seattle in 1999, opposition to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the recent Immigrant Rights Movement, and advocating for Economic and Environmental Justice. ↩

- Erasmo Gamboa was among the first wave of students to be recruited to the University of Washington in the fall of 1968. He was among the students that helped form the United Mexican American Students (UMAS) at UW, which later became MEChA at UW. His research on Mexican Braceros and Ethnic Mexican Labor in Washington’s Yakima Valley and the Pacific Northwest in general are among the seminal works produced for understanding the development and evolution of Washington State’s Ethnic Mexican and Latino communities. ↩

- For a detailed understanding of the UW Grape Boycott, see Simer’s full article: “La Raza Comes to Campus: The New Chicano Contingent and the Grape Boycott at the University of Washington, 1968-69” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project <http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/la_raza2.htm> ↩

- Oscar Rosales Castañeda, “McNair Project Proposal” Document in the Authors Personal Papers Collection, June 6, 2005. ↩

- As the northernmost state along the Pacific Coast, Washington was often the last stop along the migrant farm worker circuit. And as a result, permanent settlement took decades longer than in other regions, in turn, delaying reach of a critical mass needed for activity to take hold. In effect, it was the recognition of this transient nature among migrant farm workers that prompted organizers from the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC) to venture north to find farm workers who worked the fields in Delano, California in earlier growing seasons. The UFWOC was in the process of holding elections to represent the farm workers in Delano. As the workers ventured north, so did the farm worker movement. It was only a matter of time before the initial rumblings of this new movement shook the long dormant Latino community in Washington State, forever changing its history. ↩

- The Border Protection, Anti-terrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act of 2005 was passed by the United States House of Representatives with a vote of 239 to 182 on December 16th 2005.The bill included provisions calling for extending the border fence by 700 miles, fining unauthorized residents $3000, made U.S. citizens under the age of 18 wards of the state, and most controversial, made assisting undocumented people a federal crime, instantly criminalizing churches, schools, and community organizations nationally. ↩

- Jerry Garcia and Gilberto Garcia (Eds). Memory, Community and Activism : Mexican Migration and Labor in the Pacific Northwest. (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2005) ↩

- Jerry Garcia. Mexicans in North Central Washington. (San Francisco, CA: Arcadia Publishing, 2007). ↩

- For a detailed bibliography of sources, see: “Farm Worker Bibliography” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project <http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/farmwk_bib.htm> ↩

- “News Coverage about the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project <http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/publicity.htm> ↩

- “Chicano Movement” keyword search Civil Rights Digital Library <http://crdl.usg.edu/topics/boycott_direct_action/> ↩

- “Chicano/a Movement in Washington State History Project” teachinghistory.org <http://teachinghistory.org/history-content/website-reviews/24033> ↩

- “Students of Change: Los del ‘68” KCTS 9 Seattle <http://video.kcts9.org/video/1491354319/> ↩

As a scholar of Latino history, I am very interested to know about this project, since I had not yet come across it. I am intrigued to know more about the potential for its online presence specficially to bring the experience of marginalized groups (such as Latinos outside of the Southwest and Northeast, as the author mentions) into the historical narrative – I think some more specific stories about how that is already happening could be really illustrative and would provide strong evidence for archives to make the expense of digitizing their collections with greater frequency. Thank you for this.

I find this essay and this project particularly exciting – both for the role of the internet in accounting the history of the marginalised and considering the roles students can play in writing and documenting history online.

In our invitation to revise & resubmit your essay, we wrote:

We support the valuable public comments garnered by this essay and ask you to re-read them in detail and to consider incorporating the suggestions made therein. If you agree to revise this essay, we would like to feature it as the first in a new section about “Public History on the Web.” But in order to do so, the revised version needs to amplify specific themes to help it fit better within the scope of our volume on writing history in the digital age. Specifically, we suggest:

• Revise the introduction to provide at least a few sentences of context about the larger Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, before moving on to the Chicana/o Movement Project. The current draft assumes that our readers have heard about the former, but that’s not the case, as shown by the first comment from Natalia Mehlman Petrzela.

• Emphasize the broader argument in the introduction. Both Mehlman Petrzela and Charlotte Rochez also ask for more of the “digital history” context. We believe that this is not only “the largest archive” of the Chicana/o Movement outside of the Southwest, but more importantly, a lesson about how student-activists harnessed the power of digital tools to retell the story of a marginalized people, and to build historical awareness on the web during politically-charged current events.

• Raise the “digital discovery” story to the surface. In paragraph 8, there’s a pivot moment in the project that’s buried inside the current draft: “. . . This discovery of this article profoundly impacted how MEChA viewed the utilization of digital media in collecting this story…” This looks like a great opportunity to revise your essay to fit with our volume’s broad focus on writing history in the digital age. Tell us more about what you and other student-activists were thinking here. Why did you begin digitizing and writing for the public web, rather than compiling a more traditional paper archive, and how did this shape the broader mission?

On a similar theme, you later write: “The urban narrative existed, as many later found out, in a patchwork collection of journal articles, Masters Theses, personal document collections, newsletters, organizational papers and unpublished lithographs that remained out of the reach for people in the community not privileged enough to be enrolled at the University of Washington. As a means of addressing this issue, the UW MEChA Chapter undertook the task of centralizing and consolidating material pertinent to the history of Chicano and Latino students at the university.” But this seems less a question of physical access (anyone can walk into the public university and read a thesis on the shelf), and more about reader accessibility (it seems that you and your colleagues wrote a narrative designed for wide audiences on the web, and actively disseminated it to the public, not just where scholars might see it). If so, clearly make this point more central to the story.

• Rewrite with a more consistent first-person active voice. We appreciate your particular perspective as a student creating digital history, and we encourage you to revise your essay to eliminate the third-person passive voice. For example, as a member of MEChA, consider rewriting paragraph 4 from “this was the first time they had come together” to “this was the first time we came together. . ,” See also paragraph 11, where the current version reads: “With the project finally taking form, interest in the research slowly surfaced.” Whose interest surfaced here? We cannot tell from the rest of the paragraph. Some sections of the current essay feature first-person active voice, but it’s inconsistent.

• Cut back on the extended footnotes (nearly 1,300 words in this draft) and instead, point readers to the relevant page of your site, if possible.

• Consider raising the “Chicana/o Movement” web page screen shot (currently in paragraph 18) to the top of the essay, perhaps immediately after the introduction, to help readers who want to learn more detail. Revise the caption to read: “Click to open the Chicana/o Movement in Washington State History Project home page (http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/mecha_intro.htm) in a new tab/window.” You also can edit the image in WordPress to send readers to your URL above when the image is clicked (ask if you need assistance).

Please do your best to incorporate these recommendations into your revised essay. According to the word count at the bottom of the WordPress editing window, your current essay is 3,676 words. In order to meet our obligations to the Press, your final resubmission must be reduced to 2,500 words. Since we are suggesting some additions above, the most feasible way to begin cutting back is to shrink the notes and refer interested readers to your digital site. We understand that this is a challenge, but we believe that you can do it (and feel free to directly contact jack.dougherty@trincoll.edu if you’d would like some assistance in reaching this goal).