“I nevertheless am a historian” (Madsen-Brooks) Fall 2011

“I nevertheless am a historian”: Digital Historical Practice and Malpractice around Black Confederate Soldiers (Fall 2011 version)

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 6 I have a good deal of interest in how members of the public who are not academically trained historians “do history.” For me, then, “public history” does not mean just projects, programs, and exhibits created by professional historians for the public, but rather the very broad and complex intersection of “the public” with historical practice. Provision those occupying this intersection with freely available digital tools and platforms, and things become interesting quickly. Because setting up a blog, wiki, or discussion forum means only a few mouse clicks, and archival resources are increasingly digitized, we are seeing a burgeoning of sites that coalesce communities around historical topics of interest. Even those who have no interest in setting up their own websites can participate in history-specific Yahoo! groups, multi-user blogging communities, and genealogy sites.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Such digital spaces expand and blur considerably the spectrum of what counts as historical practice. For example, on Ancestry.com, users piece together family histories by synthesizing government records and crowdsourced resources of varying origin and credibility. Professional historians might take an active interest, then, in how digital archival and communication resources affect the spread or containment of particular historical myths.1 It is not clear, however, how these technologies aid academic historians in participating, or impede them from intervening, in these discussions. This chapter uses discourses about black Confederate soldiers to explore how digital technologies are changing who researches and writes history—as well as what authorial roles scholars are playing in the fuzzy edges of historical practice where crowdsourcing and the lay public are creating new research resources and narratives. These digital tools and resources not only are democratizing historical practice, but also providing professional historians with new opportunities and modes for expanding historical literacy.

¶ 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0

The origins of the black Confederate soldier

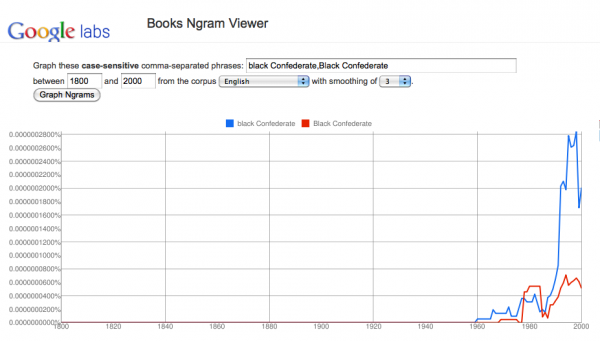

Historian Kevin Levin recently pointed out that the discourse around “black Confederates” ramped up after the release of the 1989 film Glory, which showcased the sacrifices of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry in the American Civil War. Viewers of that movie might reasonably have wondered whether there was a similar regiment fighting for the South, so it’s not surprising that an Ngram search of Google Books reveals the use of the term “black Confederate” rose dramatically after the movie’s release.2 More surprising is the term’s staying power over the ensuing two decades:

¶ 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 As we move through the four-year sesquicentennial of the Civil War, the term—its currency not yet graphable on Ngram because that tool does not search books published after 2000, nor websites—seems to be enjoying a resurgence. A Google search for the exact phrase “black Confederate” (inside quotation marks) turns up 102,000 matches.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 The typical discourse in support of the existence of black Confederates refers to them as “soldiers” or claims they served in vital support roles just behind the front lines; believers assert all of these soldiers and supporters were “loyal” to the Confederate cause, even if they were enslaved. Take, for example, Edward A. Bardill’s editorial from 2005:

Deep devotion, love of homeland and strong Christian faith joined black with white Confederate soldiers in defense of their homes and families. A conservative estimate is that between 50,000 to 60,000 served in the Confederate units. Both slave and free black soldiers served as cooks, musicians and even combatants.3

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 Such effusive praise may confuse Civil War historians, as the historical record does not support claims that large numbers of slaves and former slaves volunteered. Quite the contrary: as Stephanie McCurry highlights in Confederate Reckoning, slaves who served the Confederate army were volunteered by their masters, and on plantations slaves collaborated actively with agents of the Union army to secure their freedom.4 Some historians have asserted that some African Americans “passed” as white to enlist.5 Others have acknowledged free and enslaved blacks’ noncombatant contributions—as body servants, cooks, munitions factory and foundry workers, and nurses—to the Confederate war effort, but it appears no academic historians have subscribed to the narrative that there were thousands of black Confederate soldiers.6

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 4 The rapid spread of black Confederate soldier narratives is a function not only of proponents’ apparent desire to openly admire the Confederacy without appearing to favor a white supremacist society and government, but also of the rise of inexpensive and easy-to-use digital tools.7 Prior to the widespread adoption of the Internet, published discussion of the black Confederate soldier was contained to books like James Brewer’s The Confederate Negro, which is careful to emphasize that blacks—free or enslaved—working on behalf of the Confederacy were “labor troops” and not soldiers; Ervin Jordan’s Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia, which does not always distinguish as carefully volunteer soldiers from impressed or hired laborers; and Charles Barrow, Joe Segars, and Randall Rosenburg’s Black Confederates, which relied on the Sons of Confederate Veterans to “submit information about blacks loyal to the South” and emphasizes “many instances” of “deep devotion and affection” that “transcended the master-slave relationship” and inspired blacks to “[take] up arms to defend Dixie.”8 Today, however, the digital footprint of people who maintain there were significant numbers of black Confederate soldiers appears far larger than that of historians and others who attempt to refute the myth. (Alas, the twenty-first footprint is no longer merely digital; a textbook distributed to Virginia students in September 2010 stated that “thousands of Southern blacks fought in the Confederate ranks, including two black battalions under the command of Stonewall Jackson.”9)

¶ 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

Proponents’ use of digital platforms and sources

Black Confederate soldier and related “Southern Heritage” sites seem to arise from both a desire to tell a history suppressed by northern partisans—including the assertion that the war was fought over states’ rights, not slavery—and an explicit goal of recognizing the service of African Americans in the military. Blogger Connie Ward, for example, writes, “So they weren’t on some official muster roll and they weren’t handed a uniform and soldierly accouterments. So? What interests me is. . .did they pick up a gun and shoot at yankees? Then they need to be commemorated.”10

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 These claims are grounded in shallow, often uninformed, and frequently decontextualized readings of primary source documents that have been digitized and made available online. Take “Royal Diadem’s” reading of a ledger digitized on Footnote.com:

Captain P.P. Brotherson’s Confederate Officers record states eleven (11) blacks served with the 1st Texas Heavy Artillery in the “Negro Cooks Regiment.” This annotation can be viewed on footnote.com. See the third line on the left.11

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 In this case, Andy Hall of the Dead Confederates blog stepped up with an additional analysis of the document, noting first that the phrase “Negro Cooks Regiment,” does not actually appear on the document. Hall provides the digitized document and transcribes it: “Provision for Eleven Negroes Employed in the Quarter Masters department Cooks Regt Heavy Artillery at Galveston Texas for ten days commencing on the 11th day of May 1864 & Ending on the 20th of May 1864.”12 (“Cook” in this case refers to the commanding officer, Col. Joseph Jarvis Cook.) In a comment on his post, Hall expands on his research methods:

There are a number of cases of African American men being formally enrolled as cooks in the Confederate army and, so far as CSRs seem to indicate, formally enlisted as such. The researcher has been highlighting a number of these individual cases lately, always leaping straight from them to a universal assertion, this proves all Confederate cooks were considered soldiers. . . .

I took 20 Confederate regiments more or less at random, and went through their rosters as listed in the CWSSS, and in those 20 regiments. . .found a total of FIVE men with records of formal enlistment as cooks. . . [C]learly the takeaway is that formal enlistment of cooks in the Confederate army was not only not common, it was exceedingly rare.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 Here, Hall demonstrates an alternative, and ultimately more persuasive, reading of the document. He also illustrates how to place a source in a broader archival context.

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 This demonstration of contextualization and interpretation might be a sound response to another common sticking point on the black Confederate websites: the pensions awarded to African Americans following the war. Mississippi, Tennessee, South Carolina, Virginia, and North Carolina all eventually provided pensions to African Americans who served as noncombatants in the Confederate war effort, including soldiers’ personal servants, many of whom had been slaves.13 They were not enlisted soldiers, as it was only in March 1865 that the Confederate Congress passed, and Jefferson Davis signed into law, a bill that allowed the recruitment of blacks.14

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 2 Black Confederate websites, however, frequently cite these pension records as evidence that African Americans served as soldiers in the Confederate armed forces. Sometimes the writers imply this elision of noncombatant and soldier; Ann DeWitt (also known as Royal Diadem) makes it explicit:

Over the course of history, these men have become known as Black Confederates. Because their names appear on Confederate Soldier Service Records, we now call them Black Confederate Soldiers.15

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 3 At the blog Atrueconfederate, David Tatum blurs the line between cook and soldier, writing that a cook named William Dove appears on a muster roll that includes the term “enlisted” followed by a date.16 The digitization of wartime and postwar documents opens opportunities for more people to delve into the arcana of the past, but Tatum’s and DeWitt’s misinterpretations suggest one important role for historians at this cultural and digital moment is helping people gain the skills to interpret an era’s documents, photographs, and material culture.

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 Kevin Levin has provided the most extensive and substantive critiques of the black Confederate myth, including analyses of the major websites dedicated to the topic. On his blog Civil War Memory, Levin carefully dissects the failures of Ann DeWitt’s Black Confederate Soldiers site to distinguish between soldiers and slaves on the front line. Levin highlights the site’s utter lack of realistic context for the experience of African Americans laboring on behalf of the Confederates. For example, DeWitt’s site assumes that parallels can be drawn between “body servants”—a term she uses to denote slaves who accompanied their owners into the field—and pink- or white-collar administrative employment today: “In 21st century vernacular the role is analogous to a position known as an executive assistant—a position today that requires a college Bachelors Degree or equivalent level experience.”17 Public audiences may find history more lively if they can draw parallels with their own era, but this particular comparison effaces the deprivations faced by slaves and wartime laborers.

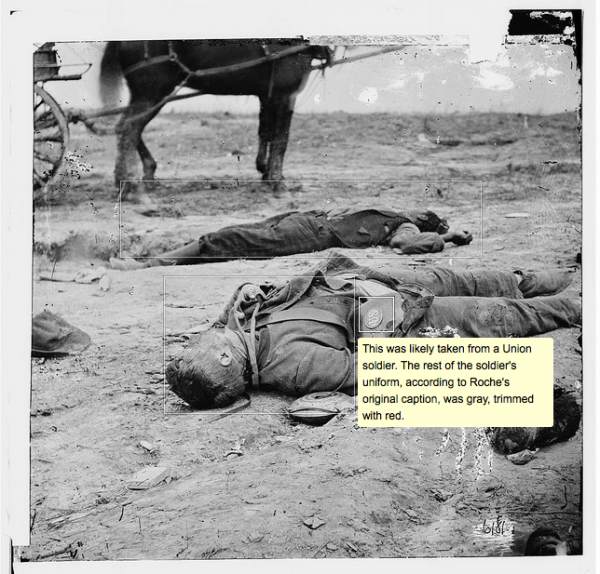

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 2 Another case of black Confederate proponents misinterpreting a primary source—or rather trusting a manipulated photographic scene—involves a photograph of a “black Confederate” “corpse.” The website Black Confederate Soldiers of Petersburg published a photo of one white and one black corpse lying on the ground, stating the “original caption” referred to them as “rebel artillery soldiers.” However, the version of the image at the Library of Congress website, as well as those I located elsewhere, is titled “Confederate and Union dead side by side in the trenches at Fort Mahone.” Further complicating website author Ashleigh Moody’s presentation of the image, the Library of Congress cites photographic detective work by David Lowe and Philip Shiman and summarizes the photo thus: “Photo shows a body lying in the background that is actually the photographer’s teamster posing for the scene. The live model appears in the same clothes in negative LC-B811-3231.” While Moody likely posted her photo prior to the discovery of photographer Thomas Roche’s duplicity, she has not yet removed the photo since its fraudulence was brought to the black Confederate proponents’ attention by Andy Hall and Kevin Levin.18 This isn’t the only case of this kind; the proponents’ credulity is echoed in their acceptance of an “1861” photo purported to be of a gray-coated “Louisiana Native Guard,” but which is actually an 1864 photo of a company of the 25th United States Colored Troops unit wearing pale blue winter overcoats—with the dark-coated unit commander cropped out of the image.19

¶ 23

Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0

Conspiracies and credentials

Many black Confederate proponents invoke conspiracies as the reason more people have not heard of these soldiers. For example, H. K. Edgerton calls the black Confederate narrative “a perspective of Southern Heritage not taught in our public schools or seen in our politically correct media.”20 The implication is that Edgerton’s and others’ websites provide a valuable public service in highlighting primary source documents and interpreting them for an Internet audience—though a brief survey of their sites often reveals conservative, and even reactionary, ideologies—while at the same time occasionally calling out as white supremacists those historians who seek to debunk the black Confederate soldier narrative.21

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Such charges highlight one significant way in which digital tools have changed the way people do history: there has been an increase in the speed with which they exchange information or, more likely in the case of proponents and dissidents of the black Confederate soldier narrative, barbs. Prior to the age of easy digital publishing tools, such unpleasant exchanges might have been kept private, perhaps e-mailed among colleagues and partisans; they would have been unlikely to see print, and they certainly would not have been made easily found by Google’s indexing. This war of words flared up tremendously in summer 2011, when the exchanges devolved into name calling, with each side accusing the other of revisionism motivated by racism.22

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 1 Milder ad hominem attacks take the form of a questioning of credentials and a disagreement about what constitutes a historian. In one weeks-long iteration of this rhetorical dance, Connie Ward takes issue with some bloggers’ insistence that real historians do history for a living: “I’m as much a historian as Corey [Meyer], [Kevin] Levin, [Andy] Hall and [Brooks] Simpson. I’m a writer of history; I work with history. No, I’m not employed to do that, but I nevertheless am a historian.” She then turns the tables, claiming these men are teachers more than they are historians: “With the possible exception of Andy [Hall], . . .what these gentlemen do for a living is. . .is teach. That makes them teachers.”23 She voices a common charge of black Confederate soldier proponents: historians are only willing to share certain facts and they are suppressing some big truth:

To be a historian at an institution of learning just means you have to show some papers that presumably verify that you’ve studied and learned.

Most people so credentialed get their papers from institutes of higher learning, which as we know, have changed over the last fifty or sixty years from places of free thought and inquiry — a setting for acquiring knowledge — to centers of indoctrination.

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0 Corey Meyer calls Ward “an amateur historian” and points out to Ward that

I nor the other blogger claim no more authority than you. . . You and yours have repeatedly shown that you do not have a grasp of the original source material that you present. However, the other blogger and I have history degrees which is not the be-all-to-end-all on the situation, but it does help us when we are working with source materials. . .we have a background understanding of how to work with those items.24

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 This exchange raises three related questions, one of which lies at the heart of this volume: what constitutes real historical practice, how are digital research and publishing tools changing that practice, and what ought to be the role of professional historians in a space where authorship has been democratized? On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog25—and they can’t be sure, either, that you’re a credentialed historian.

¶ 31

Leave a comment on paragraph 31 2

Interventions by professional historians

The most vocal opponents of the black Confederate soldier narrative in the digital realm are not employed by universities, museums, or other organizations as public historians. Corey Meyer teaches U.S. government; Kevin Levin was until earlier this year a high school teacher, and now bills himself as a “history educator” and “independent historian” who publishes in academic publications and has a book forthcoming from a university press; and Andy Hall does not disclose his profession.26 Brooks Simpson appears to be the only regular commenter employed as an historian outside of K-12 education.

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 6 Why have academically employed historians been reticent to engage in such debates? “Eddieinman” suggests that participation is pointless: “Seems to me about like space scientists devoting themselves to the Roswell incident.”27 Similarly, Matthew Robert Isham writes that countering the black Confederate soldier narrative distracts historians from more significant and rewarding varieties of public engagement during the sesquicentennial.28 Marshall Poe offers a more substantial reason for historians’ absence: such online engagement “doesn’t really count toward hiring, tenure, and promotion.”29 Furthermore, he points out, while “amateurs” have written books, authored screenplays, and created historically themed TV programs, academic historians have tended to write for an audience of other academics. The result of historians’ and their institutions’ reluctance to embrace digital media and public engagement means that, in Poe’s words, “‘users’—uncritical, poorly informed, and with axes to grind—are now writing ‘our’ history. Some of that history may be good. But the overwhelming majority of it is and will be bad.” He maintains that crowdsourcing history via the “wisdom of the crowds” fails because “the crowds are not wise.”30

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 1 My outlook on how the public “does history” online is less cataclysmic than Poe’s. I have seen enthusiasts produce interesting and useful historiography, and the ease of sharing digitized primary sources makes it easier than ever to determine the strength of the evidence presented in those narratives. Even when her historical narrative is on shaky factual ground, we can learn something useful about the writer’s—and possibly her audience’s—beliefs, habits, and values, which can also be useful to historians seeking to understand a specific public audience or contemporary cultural moment. That said, there is much at stake in the case of black Confederates, as the existence of black Confederate soldiers has been cited as proof the Civil War was not fought over slavery, but rather was pursued because of a regional disagreement about states’ rights.

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 1 So where do we go from here? Levin suggests a better sense of mission and audience would help historians determine when to become involved in discussions of black Confederate soldiers. He writes that persuading the Sons of Confederate Veterans to adopt a different perspective is a lost cause, but that mainstream audiences might be highly responsive to historians’ critiques of the black Confederate soldier narrative. In that sense, Levin points out, the effort to debunk this narrative is about digital literacy, as professional historians can provide alternative, and ultimately more convincing, interpretations of primary sources.31

¶ 35 Leave a comment on paragraph 35 0 This intervention by historians, of course, is not merely about digital literacy; each interaction provides an opportunity to educate people about historical context. Even before the high-stakes testing of No Child Left Behind, high school and college students were taking multiple-choice tests that focused on textbook content rather than historical context, on political players and events more than on the diverse everyday realities and allegiances of, in this example, nineteenth-century black men, enslaved or free, literate or illiterate, in the North, the South, and the far West. Brooks Simpson emphasizes the importance not only of sharing the quotidian experiences of blacks living in the Confederacy, but also what these people’s experiences, mundane and extraordinary, meant in the bigger picture. He tells historians that, in best practice, “you are going to make sure that, for all this talk about memory, that we remember that the Civil War destroyed slavery in the reUnited States, and that black people, free and enslaved, played a large role in that process and in the defeat of the Confederacy. Tell that story, and tell it time and time again.”32

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 4 The same digital resources that allow for the spread of the black Confederate soldier myth may provide for its containment. Deployed thoughtfully, digital technologies allow for online public historians—by which I mean, in this case, any credentialed historians who engage with the public—to focus on details that, were they merely in print, might seem abstruse or patronizingly didactic. The annotation feature on Flickr, for example, allows enthusiasts to highlight and comment on the smallest details of a photograph, asking or answering questions. “Black Confederate soldier” photos could provide a rich location for comprehensible, pixel-scale interpretation of much larger issues. Take Thomas Roche’s photo of the dead artilleryman and his own not-so-dead assistant; historians could unpack elements of the photo in ways that prove useful to students, and in many cases Civil War enthusiasts might recognize important details that escaped the historian. Similarly, audio annotation of visuals, as on VoiceThread, might provide both the lively polyvocality many netizens desire as well as a venue for the historian’s expertise, without descending into unbridled relativism.

¶ 37

Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0

Flickr’s annotation function could allow for nearly pixel-level analysis and discussion of Civil War photos.

Flickr’s annotation function could allow for nearly pixel-level analysis and discussion of Civil War photos.

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0 Considering the low opinion some reference librarians and historians have of genealogists, historians might be surprised to find genealogy forums to be self-regulating regarding the black Confederate myth.33 For example, multiple threads on the Afrigeneas Military Research Forum open with a question about black Confederate soldiers, then turn immediately to a debunking of the myth. Here Sharon Heist offers a counternarrative in a response to a post:

I’m sorry, but I have to tell you there were no Black Confederate soldiers. There has been a lot of confusion about this, but they were illegal until the very end of the war (General Order # 14, passed two weeks before Appomatox [sic].)

There were thousands who served as servants, teamsters, laborers, cooks, etc. but the fact is they were not there willingly, and to fight for the Confederate cause.34

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0 As these examples make clear, digital technologies are allowing a broader spectrum of people to research the past and write about it for a large audience. Previously, one needed the time and money to travel to archives and, in some cases, the academic credentials to study particular primary source documents. Once the research had been transformed into an article or book, there were usually gatekeepers—publishing houses, editors, and peer reviewers—to ensure some level of academic rigor. As historians, more of us need to explore new roles in the digital realm, assuming whatever responsibilities appeal to us as individuals. For some, this might mean starting a blog or podcast on an area of research; for others, it might mean publishing an ebook on how to interpret primary sources from a particular era and geographic region. Others will relish a more assertive, or even combative, role as debunkers of myths on forums or Wikipedia.

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 5 That said, our best role is perhaps not that of an authoritative figure or the “sage on the stage”; the “guide on the side” role makes more sense in the digital space. There are tremendous possibilities for collaboration with the lay public, amateur historians, and other professionals. This digital revolution is making accessible ever-larger pools of primary source materials and opening avenues for new, exiting, and sometimes challenging interpretations of those sources. Our role as historians ought to be encouraging greater, and more thoughtful, participation in historiography regardless of medium. Despite my own dissatisfaction with some of Connie Ward’s assertions about black Confederate soldiers, I would like more members of the public to share her interest in historical interpretation; I’d like to hear more people say that, despite their lack of academic credentials, “I nevertheless am an historian.”

¶ 43

Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0

About the author: Leslie Madsen-Brooks is an assistant professor of history at Boise State University.

- ¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 2

- The ethics of digital data collection are much debated—especially reading, analyzing, and citing postings on blogs and forums. My stance is that blogs and static websites are analogous to any serialized print publication; they are published online and, if indexed by major search engines, are discoverable by any Internet user. I did not post in the forums cited here, nor comment on the blogs, and thus did not influence the discussions. I cite posts only from public forums that do not require membership approval. For more, see Heidi McKee and James E. Porter, “The Ethics of Digital Writing Research: A Rhetorical Approach,” College Composition and Communication 59, no. 4 (2008): 711-49. ↩

- Kevin Levin, “Ngram Tracks Black Confederates and black Confederates,” Civil War Memory, 20 December 2010, accessed 1 August 2011, http://cwmemory.com/2010/12/20/ngram-tracks-black-confederates-and-black-confederate/. I performed an additional search on terms that may have been used to describe black soldiers prior to 1989, and particularly during the nineteenth century, including “Negro soldier,” “black soldier,” and “nigger soldier.” None of these terms, of course, isolates Confederate soldiers from Union troops. Not surprisingly, the term “negro soldier” spiked (in books at least) in the first half of the 1860s. Searches of digitized periodicals from the era for these terms proved unsuccessful. ↩

- Edward A. Bardill, “Black Confederate Soldiers overlooked during Black History Month,” Knoxville News-Sentinel 27 February 2005, accessed 5 August 2011, http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1351948/posts. ↩

- Stephanie McCurry, Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010): 265-66; 288-300. ↩

- Ervin L. Jordan Jr., Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995): 217. ↩

- For more on African Americans’ contributions to the Confederate war effort, see James Hollandsworth, Jr., “Looking for Bob: Black Confederate Pensioners After the Civil War,” The Journal of Mississippi History 69, no. 4 (2007): 295-324, and Bruce Levine, Confederate Emancipation: Southern Plans to Free and Arm Slaves During the Civil War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006). ↩

- For more on this shift in discourse and the growing acceptance of the black Confederate soldier myth by Southern heritage enthusiasts, see Bruce Levine, “In Search of a Usable Past: Neo-Confederates and Black Confederates” in Slavery and Public History: The Tough Stuff of American Memory, ed. James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006): 189-91. ↩

- Charles Barrow, Joe Segars, and Randall Rosenburg, eds., Black Confederates (Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing, 2001): 2, 4, 8. ↩

- Kevin Sieff, “Virginia 4th-grade textbook criticized over claims on black Confederate soldiers,” Washington Post 20 October 2010, accessed 5 August 2011, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/10/19/AR2010101907974.html. ↩

- Connie Ward (a.k.a. Chastain), “The Black Confederates Controversy,” 180 Degrees True South, 8 Jun. 2011, accessed 11 August 2011, http://one80dts.blogspot.com/2011/06/black-confederates-controversy.html. ↩

- Royal Diadem, posting to Southern Heritage Preservation Group on Facebook, 7 August 2011, accessed 11 August 2011, https://www.facebook.com/groups/shpg1/?view=permalink&id=271184879563396. “Royal Diadem” is a pseudonym used by Ann DeWitt. Corey Meyer, “The Leap. . .” The Blood of My Kindred, 14 April 2011, accessed 11 August 2011, http://kindredblood.wordpress.com/2011/04/14/the-leap/ ↩

- Andy Hall, “Famous ‘Negro Cooks Regiment’ Found—In My Own Backyard!” Dead Confederates, 8 August 2011, accessed 11 August 2011, http://deadconfederates.wordpress.com/2011/08/08/famous-negro-cooks-regiment-found-in-my-own-backyard/. ↩

- Hollandsworth, “Looking for Bob,” 304-5. ↩

- Bruce Levine, Confederate Emancipation: Southern Plans to Free and Arm Slaves During the Civil War, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006: chapter 5, Kindle location 1795. ↩

- Ann DeWitt, “Confederate Soldier Service Records,” Black Confederate Soldiers. n.d., accessed 12 August 2011, http://www.blackconfederatesoldiers.com/soldier_records_for_black_confederates_50.html. ↩

- David Tatum, “Myth Buster!” Atrueconfederate, 2 July 2011, accessed 13 August 2011, http://atrueconfederate.blogspot.com/2011/07/myth-buster.html. ↩

- Ann DeWitt, “Civil War Body Servants,” Black Confederate Soldiers, 1 May 2010, accessed 10 August 2011, http://www.blackconfederatesoldiers.com/body_servants_17.html. ↩

- “(Confederate and Union dead side by side in the trenches at Fort Mahone),” photo by Thomas C. Roche, 3 April 1865, Selected Civil War Photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, accessed 11 August 2011, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003000602/PP/. David Lowe and Philip Shiman, “Substitute for a Corpse,” Civil War Times 49, no. 6 (2010): 40-41. Kevin Levin, “Scratch Off Another Black Confederate,” Civil War Memory, 10 August 2011, accessed 11 August 2011, http://cwmemory.com/2011/08/10/scratch-off-another-black-confederate/. ↩

- Jerome Handler and Michael Tuite, “The Modern Falsification of a Civil War Photograph,” March 2007, accessed 10 August 2011, http://www.retouchinghistory.org/. My search on 14 August 2011 for the original version of this photo at TinEye.com turned up more instances of the cropped photo than the one with the officer. ↩

- H. K. Edgerton, “Southern Heritage 411,” Southern Heritage 411, n.d., accessed 11 August 2011, http://www.southernheritage411.com/index.shtml. ↩

- See, for example, Edgerton’s publication on his site of the article “Isn’t the Southern Poverty Law Center the Real Hate Group?” by Michael Brown, 28 July 2011, accessed 11 August 2011, http://www.southernheritage411.com/newsarticle.php?nw=2270. See also Carl Roden’s comments, as reprinted on Andy Hall’s site: “The Self-Appointed Defenders of Southern Heritage,” Dead Confederates, 3 August 2011, accessed 14 August 2011, http://deadconfederates.wordpress.com/2011/08/03/the-defenders-of-southern-heritage/. ↩

- For some examples of the vitriol, see David Tatum’s posts at Atrueconfederate, http://atrueconfederate.blogspot.com/2011/08/anti-southern-society.html (11 August 2011) and http://atrueconfederate.blogspot.com/2011/08/research-is-like-box-of-chocolates.html (10 August 2011), both accessed 12 August 2011, as well as Connie Ward’s post “The Civil War Thought Police,” 180 Degrees True South, 10 August 2011, accessed 12 August 2011, http://one80dts.blogspot.com/2011/08/civil-war-thought-police.html. ↩

- Connie Ward (a.k.a. Chastain), “Corey’s back for more,” 180 Degrees True South, 8 August 2011, accessed 13 August 2011, http://one80dts.blogspot.com/2011/08/coreys-back-for-more.html. ↩

- Corey Meyer, “Connie (Chastain) Ward Responds Again,” http://kindredblood.wordpress.com/2011/08/08/connie-chastain-ward-responds-again/, The Blood of My Kindred, 8 August 2011, accessed 13 August 2011, and “Connie (Chastain) Ward Admits: ‘History & Heritage Are Not Synonymous,’” The Blood of My Kindred, 22 July 2011, accessed 13 August 2011, http://kindredblood.wordpress.com/2011/07/22/connie-chastain-ward-admits-history-heritage-are-not-synonymous/. ↩

- See Peter Steiner’s cartoon for the New Yorker 69, no. 20 (1993): 61. ↩

- Corey Meyer, comment on “Ponderings on American Exceptionalism,” 25 September 2009, accessed 12 August 2011, The Blood of My Kindred, http://kindredblood.wordpress.com/2009/09/25/ponderings-on-american-exceptionalism/#comment-147. Kevin Levin, “Welcome,” Civil War Memory, http://cwmemory.com/about/, n.d., and “Resume,” http://cwmemory.com/cv/, Civil War Memory, n.d., both accessed 13 August 2011. ↩

- eddieinman, “Re: Simpson – Prof. Historians and the Black Confederate Myth,” 19 June 2011, accessed 4 August 2011, http://groups.yahoo.com/group/civilwarhistory2/message/173491. ↩

- Matthew Robert Isham, “What will become of the Black Confederate controversy?—a follow up,” A People’s Contest, 13 May 2011, accessed 11 August 2011, http://www.psu.edu/dept/richardscenter/2011/05/what-will-become-of-the-black-confederate-controversy—a-follow-up.html. ↩

- Marshall Poe, “Fighting Bad History with Good, or, Why Historians Must Get on the Web Now,” Historically Speaking 10, no. 2 (2009): 23. ↩

- Poe, “Fighting Bad History,” 22. ↩

- Kevin Levin, “What Will Become of the Black Confederate Controversy?: A Response,” Civil War Memory, 8 May 2011, accessed 11 August 2011, http://cwmemory.com/2011/05/08/what-will-become-of-the-black-confederate-controversy-a-response/. ↩

- Brooks Simpson, “Professional Historians and the Black Confederate Myth: Part Two,” Crossroads, 20 June 2011, accessed 11 August 2011, https://cwcrossroads.wordpress.com/2011/06/20/professional-historians-and-the-black-confederate-myth-part-two/. ↩

- For librarians’ stereotypes of genealogists, see Katherine Scott Sturdevant, Bringing Your Family History to Life through Social History (Cincinnati: Betterway Books, 2000): 166-70. ↩

- Sharon Heist, “Re: AA Confederate Solider (sic) Info,” Afrigeneas Military Research Forum, 24 October 2004, accessed 9 August 2011, http://www.afrigeneas.com/forum-militaryarchive/index.cgi/md/read/id/1553/sbj/aa-confederate-solider-info/. ↩

The democratizing nature of the Web is not a new topic in the realm of digital humanities. What is given less attention is how this democratization changes the way history is produced and disseminated in the public realm. Leslie Madsen-Brooks is particularly interested in the way the Internet allows a non-academically trained public to “do history,” and the relative absence of professional historians in this growing online dialogue. To illustrate her arguments, she uses the propagation of the black Confederate soldier myth in online forums like blogs, websites, and discussion boards.

Refraining from chiming in on the issue that serves as her example (something that is hard for a Civil War historian such as myself to do), I must mention that the use of the black Confederate argument is especially effective. The Civil War is a subject with many lay followers, who, as Madsen-Brooks points out, are markedly more vocal online than their professionally-trained associates. She succeeds in demonstrating what is at stake when academics refrain from becoming involved with the “Internet audience.”

One of the questions raised in this article is similar to those presented in connection with the existence of Wikipedia: what do we, as professional historians, do about the “bad” or unsubstantiated histories that are made widely available due to the “rise of inexpensive and easy-to-use digital tools?” (¶9) In an age where almost anyone can publish in an online space, do historians have a duty to engage with this content? While not going so far as to label it a mandatory obligation, Madsen-Brooks insists that “an important role for historians . . . is helping people [members of the public] gain the skills to interpret an era’s documents, photographs, and material culture” (¶20). While this is a pleasant thought, one has to wonder what kind of historian has time to police the web in such a fashion?

Madsen-Brooks is not ignorant of this problem, and provides excerpts from the conversation as it has appeared in academic circles. Most telling—and representative of the reasoning nearly all academics cite—is Marshall Poe’s explanation that a digital presence “doesn’t really count toward hiring, tenure, and promotion.” But by staying absent from these online conversations, historians are leaving the writing of history to public users who are “uncritical, poorly informed, and with axes to grind” (¶32). Despite the seriousness of this issue and its implications for the future of history on the web, Madsen-Brooks does not offer any suggestions as to how to improve the situation. In her defense, it is not a matter which is easily resolved. How can we make sure that Internet presence is considered as part of tenure?

“Sustaining Digital History,” a meeting held at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln last fall, attempted to address these issues by gathering authors, peer reviewers, and journal editors together to discuss the ways in which digital scholarship might be incorporated into the existing print-based journal world. While not directly related to the issues undertaken in this article, it is indicative of developments that are taking place to raise awareness of digital forms of scholarship. More of these dialogues need to happen in order for institutions to understand the value of scholarly work in the online environment. The problem facing us at the moment is that creating a “digital footprint” takes time away from professional pursuits. Until creating digital scholarship, composing historically-driven blog entries, or participating in online historical debates counts as part of those professional endeavors, I think the trend of few professional historians on the web will continue.

But back to Madsen-Brooks’ assertion that historians should be actively-participating with the Internet audience, she suggests the need for “online public historians”—“credentialed historians who engage with the public” (¶36). While I do not think she intended it this way, this comment triggered in my imagination a new brand of historians. Most of the discussion about digital history centers on University academics. But what about historians who work outside the academy? As an historian who plans to work in the public realm, I wonder if we might not consider this part of our relations with and education of the public? If educating or interacting with the Internet audience is not a job for academic historians, is there room for a new kind of public historian?

Putting these questions of time and tenure aside, how can historians participate online? Madsen-Brooks urges more historians to “explore new roles in the digital realm” by assuming “whatever responsibilities appeal to us as individuals” (¶41). She suggests opening a blog or podcast, creating an e-Book, or managing content on public forums like Wikipedia. But is joining already-established networks the best way to go about this? Joining the blogosphere will only result in historians creating works that look like the “amateur” publications. What is lacking here is a sense of legitimacy, an elevation of the work of academics with “a background understanding of how to work with [historical] items” over that of a non-credentialed public (¶28). Perhaps we need more “born-digital, open-review” venues such as “Writing History in the Digital Age.” Or perhaps an academic blogging platform that requires registration or credentials to participate.

There appears to be no definitive answer to the questions posed in this article. However, Madsen-Brooks’ thoughtful presentation of the complications that arise with the democratization of the Web are an important addition to the conversations that will eventually lead to a new role for historians in the digital age.

Leslie Madsen-Brooks’ essay, “I nevertheless am a historian,” is an excellent way to start, framing central questions for the collection in the context of a broadly accessible and hotly contested test case. Her themes (“what constitutes real historical practice, how are digital research and publishing tools changing that practice, and what ought to be the role of professional historians in a space where authorship has been democratized?”) are key to the collection as a whole. As a non-historian, though, I was left with some puzzlement about what seemed to be under-interrogated references to “academic credentials.” What constitutes a “credentialed” historian? Does this require a doctorate? Are there alternative routes to recognized/recognizable authority? Would public historians and museum workers with master’s degrees or significant work experience be considered adequately credentialed to adopt the “guide on the side” role Madsen-Brooks advocates — or would these people remain in the group of “other professionals” with whom those addressed in her last paragraph might collaborate? I suspect the central points of this excellent essay would not only be strengthened but made more applicable to disciplines outside or on the edges of history, if some of the field’s internalized assumptions about credentialing were addressed head-on.

This essay tackles an exceedingly interesting question for historians–when and how might they intervene in the digital environment over questions of authenticity, authority, and/or interpretation. The black Confederate movement develop in tandem with the Internet. In 2000 when Alice E. Carter and I published The Civil War on the Web, a critical guide to the way the Civil War was portrayed on the web, we received almost immediately a flurry of challenges from a group of re-enactors in Terrell’s Texas Cavalry brigade because we had not included their site among our 100. The site, it turned out, featured documents purporting to provide evidence of so-called black Confederates. Most of the documents were from the Official Records and, in their original context, referred to impressed Confederate laborers. The members of this organization began sending me emails, however, suggesting it was liberal academic bias not to see what they saw in these documents–what they called a “rainbow coalition” of the South’s independence hungry soldiers and cause. They claimed then that academics were suppressing the real story of the war. One email was signed by a falsified name of an alleged emeritus professor of history at Yeshiva University–no such person was ever employed at the school. In any case the group moved on as I recall and their attention became focused on defending John Ashcroft. The point is that digital information can be manipulated and identities concealed in the online space.

I found little reasoned discourse in my private email correspondence with the fellows of Terrell’s brigade. There was a veneer of initial courtesy and over the course of this correspondence a rapid escalation into accusation and diatribe. So, I’m skeptical based on this experience of Leslie Madsen-Brooks’ suggestion that we participate more and become the “guide on the side.” (Kevin Levin was a student of mine in a teacher’s seminar at the University of Virginia, and he has done more work on this issue than anyone. His suggestion makes a great deal of sense to work on the broader questions before the public.) One of the reasons that this issue has some bearing is that the largely white American narrative of the Civil War elides the contributions of African Americans, or the experience of African Americans. I would ask her to press more on the question of how to deal with the question of rip-mix-burn culture and the provenance of, and interpretation of, historical materials. The online space excels at manipulation. Are historians working against the grain, the underlying nature of the medium? If so, what can be done to take more advantage of the medium to give greater context to this subject–see for example the Virginia Historical Society runaway slave role playing exhibit–fully immersive.

There are a variety of places to tackle this point (both in this essay and throughout the project) but I would like to see a more extensive awareness of the larger and prior domains within which this approach to digitization and the circulation of historical knowledge sits. Meaning, Madsen-Brooks in this first paragraph mentions this wider sense of the “production of history” but then quickly confines it to digital practices and media. I think it’s fine for this essay (and the wider project) to have that focus but the question of how historical knowledge circulates and is produced by publics and individuals beyond the academic guild of historians is a question that precedes the digital–Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Raphael Samuel, David William Cohen, John Gillis, Joanne Rappaport and many others come to mind quickly in this context. I think the contributors need to do this kind of situating early in their analyses in order to sharpen the sense of what digitization changes (or does not change) about the production of history in circulations beyond and intersecting with the academy.

Thanks so much for your comment, Bethany. I absolutely used shorthand where I should be more forthcoming, and I recognize some irony in encouraging non-credentialed historians to tackle history at the same time as I insist on some kind of credentialing. The recent discussion of badges comes to mind. . . Thanks again!

Thanks so much for your insightful and thorough comments, Kaci. I wish I did have an answer to the question of how to differentiate “credentialed” (an adjective I realize I’ve left pretty vague here) historians’ work online from amateur historians’ contributions. My own department’s guidelines for tenure and promotion do recognize “alternative” contributions to traditional scholarship, but what exactly constitutes significant and relevant production is evaluated case-by-case; there aren’t clear delineations between what counts and what doesn’t. As an assistant professor on the tenure track, I’d love to see some clearer advice on such matters emerge from our professional associations.

Because I mentor many public history grad students, I’d also like to see more discussion (beyond talk of “Plan A” vs. “Plan B”) about how to prepare these emerging professionals for a digital age. How much of their training should include technological literacy and skills, and how much of it critical thinking about the public use of technology to “do history”?

Thank you, William, for sharing your own experiences with the Black Confederate soldier proponents. Perhaps I am being too generous in suggesting we work with them rather than always be in combat against them, and maybe I could have selected a better example to demonstrate a place where professional historians could enrich the understanding of amateurs pursuing reasonable historical leads.

Mainstream genealogy comes to mind as one place where historians might serve as guides on the side. That said, at a recent regional history conference, it became clear to me that many genealogists would see such offers of assistance as intrusive, as they are the experts in their domain. That discussion has made it more difficult for me to imagine spaces where such collaboration could occur. Perhaps citizen science offers one model?

You’re absolutely right–this essay does need greater contextualization. In part, my own scholarly myopia explains the omission. I did become a scholar in the digital age, and I don’t have any degrees in history myself–mine are in English and cultural studies–which means I also don’t have the historiographical background that might ease such a contextualization. Another issue in this elision is we are limited to 5,000 words, and I have to admit in my own revisions, I prioritized Black Confederate examples over context. When I revise the essay, I’ll look for ways to provide some sense of the conversation about knowledge circulation and democratization prior to the digital age. Thanks so much for your comments.

Thanks to everyone for your comments. As a veteran of creative writing workshops, I’ve been sitting back and “listening” to your contributions rather than engaging with them all along (as I fear I would sound–or be–defensive), but please know that I’ve been finding them incredibly helpful and insightful.

I think it would be great to have some further explicit discussion of ontological and epistemological issues within the essay.

It might be interesting for there to be some dialogue between you and Wolff (especially paragraph 5) regarding how we perceived memory and history.

In our invitation to revise & resubmit this essay, we wrote:

Explicit attention to three particular themes would strengthen this essay’s contribution to the volume as well as to the wider discourse of digital history. First, you should do as you suggest in your own response to comments, i.e. to play with (or at least refer to some of) “the philosophical implications of an imagined or actual past” as they emerge in this essay. Secondly, as Bethany Nowviskie notes (and as you yourself acknowledge in a comment thereto), the premise of this essay requires an interrogation of “academic credentials” as a source of legitimacy and authority. Both of these are themes common to other essays in the collection, and it is important to address them here – preferably even with reference to those other essays. Finally, we ask that you especially consider William Thomas’s prompt for more critique of the engagement you call for, namely: “[H]ow to deal with the question of rip-mix-burn culture and the provenance of, and interpretation of, historical materials. The online space excels at manipulation. Are historians working against the grain, the underlying nature of the medium? If so, what can be done to take more advantage of the medium to give greater context to this subject–see for example the Virginia Historical Society runaway slave role playing exhibit–fully immersive.”

See also other comments on your essay in the Fall 2011 web-book. Please do your best to incorporate these recommendations into your revised essay. According to the word count at the bottom of the WordPress editing window, your current essay is 4,844 words. In order to meet our obligations to the Press, your final resubmission must not exceed 5,000 words.

As a history major in college, I admit that I don’t know a third as much as any regular historian, but I have done research on African American Confederates. I’m also a Civil War reenactor, so it’s quite a controversial issue. While there were definitely more black Union soldiers, it seems to me that there were at least some instances in which African Americans fought as soldiers in the Confederate military. To deny this would be to discredit vast numbers of period quotations and journal entries and newspaper articles regarding the matter. While there weren’t 1000s of black Confederates, there were a number. To deny this would be revisionist.