Learning How to Write (Lawrence)

Learning How to Write Analog and Digital History (2012 revision)

Creating a robust historical work has long been an exercise in extensive research, careful interpretation, and the crafting of arguments with tight prose and a solid evidentiary base. Cast as an objective enterprise in the nineteenth century, doing history has since become infused with research approaches and theories of scholarship that span the humanities and social science disciplines.1 Yet, historians have largely remained solitary researchers and writers, often developing idiosyncratic but fruitful methods of research, analysis, and writing in their production of knowledge.2 Learning how to “do history” can feel like learning through osmosis. The training is often oblique with little direct instruction, but with multiple opportunities to practice archival research, “document analysis,” historical conversation, and writing. One eventually figures it out, but until one has read enough of the secondary literature, spent scores of hours doing archival research, and writing mini-monographs that peers read and critique, the history experience is frequently one of consumption. Even when one transforms from a knowledge consumer to a knowledge producer, the exposure of one’s work to the outside world is quite limited, unless the burgeoning historian publishes their work digitally in public spaces such as on blogs, on Wikipedia, or on their own websites. With this in mind, I set out to develop a course on the histories of education that featured student work in old and new media.

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

Design of Course & the History Signature Pedagogy

In the fall of 2010, I taught, for the first time, a graduate seminar entitled, EDU/HIST-596: Histories of Education.3 Though this course attempted to survey the histories of education in North America over the last 500 years, the primary emphases of the course were to evaluate the historiography of education history and experiment with different historical research and writing methods and formats.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 With the goal of helping students learn how to think historically4 by sourcing evidence, developing inquiry questions, weaving context, and evaluating historical significance, I designed Histories of Education around two questions: when did education begin in the Americas?,5 and how have historians of education framed the field of study? The readings were selected to jar students’ preconceptions about who constructed education and how they went about it beginning with a close reading of Urban and Wagoner’s survey text, American Education: A History.6 The final segment of the course was devoted to reading autobiographical accounts of individuals’ educations.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Though reading and discussion were a large part of the course, this essay focuses on the written work students created. They experimented with three different platforms of historical writing. First, students produced an analytical critical review of two scholarly articles or books against the backdrop of a common question or theme. Students were to look in academic journals and The New York Review of Books for examples of compelling reviews. Second, students created a brief contribution to Wikipedia in order to situate themselves as knowledge producers to publicly share what they learned with the world and to evaluate Wikipedia as a source of information.7 Third, students produced an online, publicly available digital history on a topic of interest which they began researching with their Wikipedia contribution. Unlike their Wikipedia contributions, though, students did original research for the digital history project and had to develop not only the textual history, but also its online environment.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 This study examines written work of five out of the nine students in the class students in the class. After students submitted each piece, the class debriefed the research, writing, and revision process, articulating challenges and breakthroughs. In every class meeting throughout the semester, students reported on the status of their long-term digital history projects and offered each other ideas for possible source material or ways of analyzing what they had found. By the time class members presented their digital histories at the end of the semester, the degree of familiarity they had with each other’s interests and research afforded a hearty discussion about the construction of each digital history project. An anonymous follow up survey was sent out to participants via Google Docs8 several months later to gather more information about each student’s writing and revision process. Though this sample is small and should not be taken as representative, it does reveal practices, considerations, and points of confoundedness that other historians, student or professional, might well experience as they move from analog to digital platforms and audiences.

¶ 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

The Critical Review

The critical book or article review is a staple not only in the history profession as numerous academic journals illustrate, but also in the graduate training of future historians. Learning how to write an analytical, pithy review hones one’s ability to evaluate texts in terms of their argument and use of evidence and to place a text in relation to the broader field of study. In crafting an analog critical review for the class, students evaluated two texts that we had read or that they had found on their own and appraised the significance of each piece within the history of education or another subfield of history. Students submitted their 1200-1500 word reviews in standard essay format through Google Docs, and several published their reviews on the course website after revision.

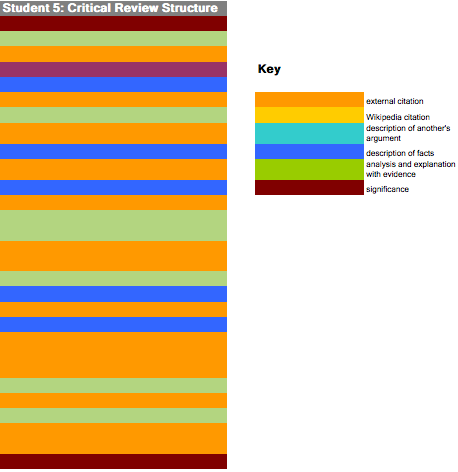

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Students reported that writing the critical review was very familiar—analyzing texts was almost automatic for them, and they were also comfortable taking a comparative approach. Most spent two to four hours initially drafting the review, and most revised their reviews twice before submission with a day’s lag time in between each revision. The speed of the initial drafting and the structure of students’ reviews bears out their stated familiarity. As the visualization of Student 5’s critical review structure illustrates below (see Figure 1), students typically introduced the authors and central arguments of the secondary sources examined within the first two paragraphs of their reviews. The structure of the reviews then oscillated between descriptions of the authors’ arguments and use of evidence, each student’s own analysis, and citations referencing specific ideas or phrases in each source. The sequence of each student’s analysis varied, but each critiqued the two sources in relation to one another, identifying commonalities, gaps, and shared or disparate evidence. Students also explained each author’s research and/or reporting methodologies, which in many cases, could only be uncovered through an extremely close inferential reading. Students closed their critical reviews with statements about the significance of each author’s contribution.

¶ 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0

Figure 1. Critical Review Structure, Student 5. Created by Adrea Lawrence for this analysis and essay using Microsoft Excel.

Figure 1. Critical Review Structure, Student 5. Created by Adrea Lawrence for this analysis and essay using Microsoft Excel.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 Though the structure of the students’ reviews follows convention, crafting such reviews is no easy task. In order to contextualize a piece, assess its significance, or identify gaps in study, it is necessary to have read widely and engage a synthetic understanding of a research area. Understanding this, it is not surprising that most students aligned their critical reviews with their digital history project topics and Wikipedia contributions, opting to search for and select articles to review rather than examine those already read for class so that they could build a body of factual and interpretive knowledge source by source throughout the semester. Through this process, students were thinking historically by sourcing the materials they examined, developing a complex set of questions to further probe each source, and weaving together a contextual backdrop based on authors’ normative and descriptive assumptions as well as students’ own positionalities.9

¶ 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

The Wikipedia Contribution

Unlike the critical review, contributions to Wikipedia10, the online, crowd-sourced encyclopedia, are not (yet) staples in the professional training of historians. Over the last decade, Wikipedia has grown to include nearly 4 million articles in English. For many, it has become the default source and starting point for learning about something. In his 2004 study of Wikipedia as a secondary source, historian Roy Rosenzweig noted that this reference tool confounds many of the assumed trademarks of historical scholarship, such as singly authored, detailed works; individual recognition for scholarly work; and cogent narrative analysis that evaluates a subject’s historical significance. Original research and presenting a particular point of view—practices that are valued among historians—are eschewed on Wikipedia, which promotes instead secondary research and descriptions of others’ arguments. Even with these practices, Wikipediais widely visited and widely edited, offering transparent discussions between editors about why particular sources were chosen and presented in a particular sequence or manner. 11 Working with Wikipedia from the inside as a contributor can thus expose students to debates over source material and their interpretations.

The “Wikipedia Article & Tracking Report” assignment in my Histories of Education course is modeled on the one that Jeremy Boggs created for his students. I assigned the Wikipedia contribution to my students for two reasons: to demonstrate that students could be and were knowledge producers and to have students critically examine Wikipedia as a secondary source which purports to publish descriptive, fact-only material.12 Students in my class had to conduct research, including finding a topic that ideally corresponded to their digital history project and was a desired article on Wikipedia as noted on the education stubs page, which lists articles that the editors wish to see expanded.13 Like Boggs, I asked my students to write a 500 word article or contribution that included footnoted references to two books or scholarly articles, two external websites, and two internal Wikipedia pages. Once they had posted their contribution, students were to share the URL with me and do everything possible to prevent their contributions from being deleted. After a month, they were to describe their experience through a tracking report, detailing how many edits the post received, what types of edits they were, discussions they had with other editors, and efforts they made to prevent their article from being deleted. Students also reflected on what they learned about Wikipedia as a source from an insider perspective.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 Of the five student contributions examined here, three students created their own unique articles on Wikipedia, while two students added content to existing pages. As with their critical reviews, students structured their Wikipedia articles in a manner that toggles between the presentation of another’s idea, argument, or set of facts, and citations to supporting secondary sources. Rather than provide their own analysis, however, students described the debates or arguments that others had on a given topic (see Figure 2).

¶ 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0

Figure 2. Critical Review and Wikipedia Contribution Structures, Student 5. Created by Adrea Lawrence for this analysis and essay using Microsoft Excel.

Figure 2. Critical Review and Wikipedia Contribution Structures, Student 5. Created by Adrea Lawrence for this analysis and essay using Microsoft Excel.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 Acutely aware of their own limitations as emerging scholars in a discipline that has idealized the lone historian researching and writing exhaustively on a subject, the thought of historical collaboration and intellectual ownership of historical writing with other anonymous contributors felt unnatural to seasoned history students. Students were surprised that people looked at and presumably read their contributions. Students’ doubts about anyone reading their work were unfounded as shown in Table 1. Even the most modest number of total views since the article posting—925—reflects a readership that is much more extensive than what students could expect to receive in a classroom setting. In general, the number of edits to a page since students posted in October 2010, suggests a sustained interest in the page topic. So, too, does the fact that all but one of the articles were flagged for further development with editor requests for additional citations and revisions that attend to the neutral point of view policy. All told, the number of page views of Wikipedia articles students created or contributed to totaled 70,244 between October 2010, when students made their posts, and August 5, 2011, when this essay was drafted. Though these data are limited and should not be considered representative, they confirm Rosenzweig’s contention that Wikipedia is an important source for people who want to learn more about a topic and share their research with others in spite of the elements that run counter to the practice of professional historians.

¶ 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0

Table 1: Wikipedia page views and revisions for five sample student articles, 2010-11.

Table 1: Wikipedia page views and revisions for five sample student articles, 2010-11.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 When debriefing this assignment, students reported that they not only viewed Wikipedia as a secondary source worth consulting, but also that they began viewing secondary sources all together more critically. Most students began fact-checking other pages on topics about which they considered themselves to be proficient. And, students made concerted efforts to present material in a convincing and verifiable way to avoid having their posts deleted well after the assignment for class was due. Contributing to Wikipedia became, effectively, a series of self-sustaining, creative intellectual acts.

¶ 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0

The Digital History Project

Building on students’ experiences writing conventional critical reviews and more unconventional Wikipedia articles and posts, the digital history projects that the Histories of Education students undertook sought to explore whether the medium did, in fact, become the message,14 or if the message itself might help a creator construct the medium. As students reported weekly on the development of their digital history projects and continued to build their research expertise, the shape each project took was formed inductively from the research content. Indeed, one of the primary concerns that emerged was how to capture and present their research in ways that were true to their inquiry experiences and methods.

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 For most students, creating a project in an online, public environment was new and intimidating; only one student had taken the graduate level digital history course offered at AU. And while others had blogged, creating an academic, historical work online felt entirely new. The constraints students faced in creating a digital history project were typical of those faced by historians doing analog history. Like professional historians, students reported that they spent much of their time trying to figure out how to cull their research and hone in on the emerging story. How do you know what is important? How do you analyze the sources in relation to one another in a systematic and valid way? How do you know your interpretation is reasonable? And, how do you tell a story—how do you craft a history—that is interesting and significant?

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 These questions were not resolved in writing for Wikipedia; they were magnified. The digital aspect of the project likewise brought forth an existential predicament: what if people don’t want to read long-form history online? As one student said, “[w]ebsites aren’t supposed to be wordy.” If this is the case, then what does that mean for the stories and narrative analyses that historians create? How are they to be organized and told? What does this mean for the profession, let alone individual projects? It also brought forth an epistemological conundrum—the realization that people don’t necessarily read in a linear fashion online as they presumably do with an article or book. Students grappled with these issues head on in developing their digital histories, and their experimentation and final project products are instructive in highlighting the ways in which digital histories are different from analog articles and monographs.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 Creating a traditional 5000 word essay was not terribly appealing to students, particularly when the online environment allowed them to provide a range of primary, multimedia sources to readers instead of just citations. So, students created websites and interactive timelines that attended to their curiosity in playing with different ways of doing and presenting history while meeting customary scholarly expectations.

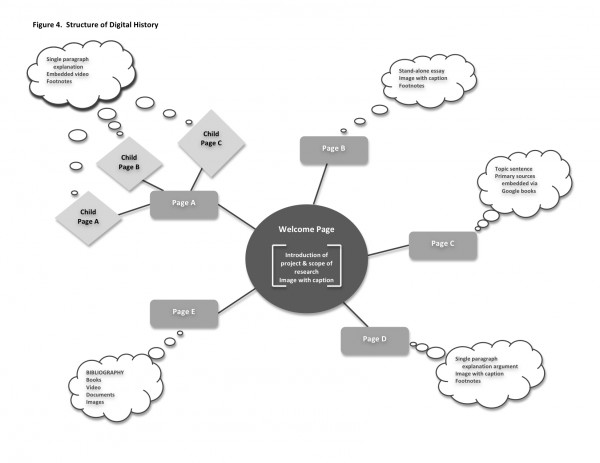

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 As is common with analog histories, students organized their digital history content thematically or chronologically. Though each website features a welcome or home page that explains the central questions and scope of the given study, in general, students chose two different methods of organizing their projects: a series of stand-alone essays or a disassembled linear essay. Two students developed websites using the WordPress15 platform, creating a series of interlinked, distinct essays. Both of these sites have discrete pages for each essay, which students wrote with a general audience in mind. And each site also has derivative, or child, pages stemming from several of the primary pages that feature particular essays oriented around a theme. The pages on each site can be read in any order, and both sites use customary methods of documentation through footnotes or parenthetical notes. In fact, the author of one site gives the reader permission to “click around, explore, and gain a better understanding of how exactly we did get here.” (See Figure 4).

¶ 22

Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0

Figure 4. Sample Structure of Digital History. Created by Adrea Lawrence for this analysis and essay using Microsoft Word.

Figure 4. Sample Structure of Digital History. Created by Adrea Lawrence for this analysis and essay using Microsoft Word.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 The second method of organizing the digital history projects was through disassembly, or carving up a linear essay into distinct pages that include the same content: a title, a statement about the argument, and the corresponding section of text to support that argument. The introductions of these websites read as introductions to cohesive essays, each providing a strong argument and grounding research questions. Each site features multiple pages that comprise sections of the overall essay. While two students acutely felt the challenge of not being able to control the order in which the viewer reads the pages as their sites utilize a horizontal navigational bar across the top linking each discrete page, another student found a possible remedy through the use of the vertical navigation bar. Students’ concern with the order in which viewers read pages originates in the epistemology of their projects as disassembled yet potentially cohesive essays interspersed with primary source evidence. They constructed their text and analysis in a particular way and hoped that they would be read as such.

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 The question of how to present an argument and a cogent narrative in a digital, multimedia format is a daunting one for historians, and seemingly few shared protocols exist such that they might be considered mainstream or stable in a relatively new and dynamic online environment. One student embraced this. Matthew Henry, who created the Hollywood Made Kids digital history project, also used the Prezi.com presentation tool to design a non-linear, motion-driven companion timeline, titled, “Censorship, The Payne Fund Studies and Hollywood’s Influence on Children.”16 Using the forward and backward buttons, the viewer can zoom in to a pre-directed portion of the screen. The section shots, so to speak, have the capability to show embedded video and audio files, and the presentation creator visually moves the viewer from section to section. The one-line headings and still or moving images, in effect, become figuratively superimposed on one another, telling a story that the presentation creator has constructed.

¶ 25

Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0

Figure 5. Prezi Screenshot

Figure 5. Prezi Screenshot

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0 Related to the presentation of a clear historical narrative was the issue of opening up the historian’s constructive processes for public comment. One of the most interesting conversations that emerged during the final presentations revolved around whether or not to leave the comments feature of the websites live. Having experienced open commenting and editing on Wikipedia, students seemed to have faith that comments posted on their sites might well be insightful and constructive. One was hesitant for aesthetic reasons—she didn’t want to clutter the site. Others were hesitant for fear of vandalism or extremist views or critique. The two students who had left the comments feature open on their sites countered that it might be a good idea, noting that the comments have the potential to provide an opportunity to rewrite, correct errors, and engage in a public discourse about a topic that greatly interested them as they experienced on Wikipedia.17 Such transparent conversation and attention to writing and its organization were complemented by the visual environment.

¶ 27

Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0

Conclusion

The student work examined above affords a fertile view into the nature of the construction of histories from the vantage point of emergent historians. Most fundamentally, students’ concern for the integrity of the historical narrative, its structure, its documentation, and its transparency or opaqueness surfaced, to a large extent, through discussions about audience. Students found that their love of the story conflicted with their intellectual desire to be open with possible readers. But not knowing who their possible readers were or how they would proceed through students’ digital histories, suggests that the students learned the individualistic nature of historical scholarship early in their training. Students’ concern with the changing epistemological nature of historical construction intensified as they moved from a familiar analog environment to the ever-changing digital one. Developing protocols for identifying readers of digital histories as well as consulting the emerging scholarship of cognitive psychologists and specialists in informatics and literacy are necessary. Additionally, the question of the long-term accessibility of digital scholarship remains unanswered. Finally, students’ experimentation with writing for general audiences and creating a digital history suggest the need for explicit training in both public history and web or graphic design. The orientation of students’ scholarship in Histories of Education was that of a public good; their experiences underscore the changing forms and norms of doing history.

¶ 28

Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0

About the author: Adrea Lawrence is an Associate Professor in the School of Education, Teaching, and Health and affiliate faculty in the History Department at American University in Washington, DC. Lawrence’s research extends from the policy histories of American Indian education to research methodologies that include historical, ethnographic, and spatial history methods.

- ¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0

- Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The “Objectivity Question” and the American Historical Profession(Cambridge University Press, 1988). ↩

- Dougherty and Nawrotzki, eds., Writing History: How Historians Research, Write, and Publish in the Digital Age, Fall 2010, http://writinghistory.wp.trincoll.edu. ↩

- Adrea Lawrence, Histories of Education, Fall 2010, American University, Washington, DC, http://www.adrealawrence.org/courses/edhistory/fall2010/. ↩

- Bruce A. VanSledright and Christine Kelly, “Reading American History: The Influence of Multiple Sources on Six Fifth Graders,” The Elementary School Journal 98, no. 3 (January 1998): 239-265; Sam Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001). ↩

- Donald Warren, “American Indian Histories as Education Histories” (presented at the American Educational Research Association, Denver, CO, 2010). ↩

- Wayne Urban and Jennings Wagoner, American Education: A History, fourth edition (New York: Routledge, 2009). ↩

- This assignment is based on Jeremy Boggs, “Assigning Wikipedia in a US History Survey,” Clioweb, April 5, 2009, http://clioweb.org/2009/04/05/assigning-wikipedia-in-a-us-history-survey/. ↩

- Google Documents, http://docs.google.com. ↩

- Lendol Calder, “Uncoverage: Toward a Signature Pedagogy for the History Survey,” The Journal of American History 92, no. 4 (March 2006): 1358-1370, http://jah.oxfordjournals.org/content/92/4/1358. ↩

- Wikipedia, http://www.wikipedia.org. ↩

- In this volume, see Shawn Graham, “The Wikiblitz,” and Robert Wolff, “The Historian’s Craft, Popular Memory, and Wikipedia,” Writing History in the Digital Age. See also Roy Rosenzweig, “Can History Be Open Source?,” The Journal of American History 93:1 (2006), 117-146, para. 1-3, 13, 39-41, 62, 70, http://jah.oxfordjournals.org/content/93/1/117; Lisa Spiro, “Is Wikipedia Becoming a Respectable Academic Source?,” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities: Exploring the Digital Humanities, September 1, 2008, http://digitalscholarship.wordpress.com/2008/09/01/is-wikipedia-becoming-a-respectable-academic-source/. ↩

- Boggs, “Assigning Wikipedia in a US History Survey.” ↩

- Wikipedia, “Category:Education_stubs,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Education_stubs. ↩

- Marshall McLuhan, “The Medium is the Message (1966),” in Understanding Me: Lectures and Interviews (Cambridge, M.A.: MIT Press, 2003), 76-97. ↩

- WordPress, an open-source web publishing tool, offers free hosting at http://www.wordpress.com and free software from which to run a website on one’s own server at http://www.wordpress.org. ↩

- Matthew Henry, “Censorship, The Payne Fund Studies and Hollywood’s Influence on Children,” December 2010, http://prezi.com/rdkntzm6spjz/censorship-the-payne-fund-studies-and-hollywoods-influence-on-children/. ↩

- “EDU-596 Digital History Presentations,” discussion with Adrea Lawrence, December 9, 2010. ↩

Comments

Comments are closed

0 Comments on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

0 Comments on paragraph 15

0 Comments on paragraph 16

0 Comments on paragraph 17

0 Comments on paragraph 18

0 Comments on paragraph 19

0 Comments on paragraph 20

0 Comments on paragraph 21

0 Comments on paragraph 22

0 Comments on paragraph 23

0 Comments on paragraph 24

0 Comments on paragraph 25

0 Comments on paragraph 26

0 Comments on paragraph 27

0 Comments on paragraph 28

0 Comments on paragraph 29